Courtesy of Landscape News

Written by: Monica Evans

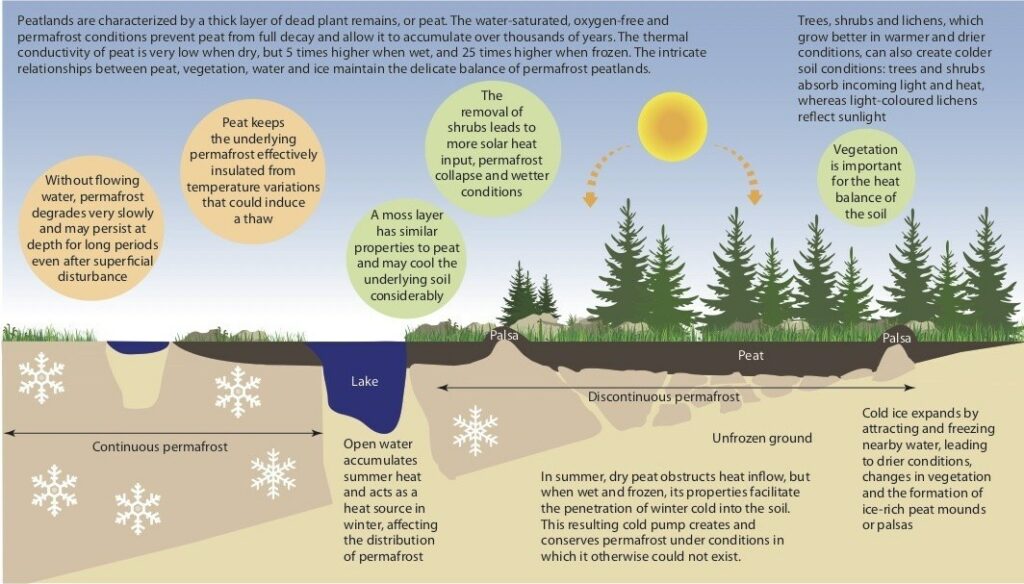

Across the northern and southern extremes of our planet, vast swathes of land amounting to around 30 percent of the Earth’s service are frozen year-round in a substance known as permafrost: soil, rocks and sand bound together by ice. In many of these areas, a layer of peat – carbon from organic material that couldn’t rot away due to the cold – sits on top of the permafrost and prevents it from melting.

These landscapes might look bleak and unproductive to untrained eyes, but they’re in fact crucial players in climate change mitigation due to their immense carbon storage. It’s estimated they contain over 8 percent of the entire global below-ground carbon pool.

But these ‘quiet heroes’ of carbon sequestration are under threat. Temperatures in the Arctic are rising twice as fast as in the rest of the world, and the trend is projected to accelerate in the coming decades. That means permafrost soils are starting to thaw, which scientists believe could cause a runaway greenhouse effect if left unabated.

This makes the peat covering the permafrost even more precious, says Dianna Kopansky, a UN Environment expert on landscapes and biodiversity and the coordinator of the Global Peatlands Initiative. “They act like a blanket, keeping that earth cold,” she explains. “They also act as a very unique kind of pump, sucking in the cold because of their wetness and the way the hydrology works.” Scientists used to think that once permafrost thawed it was gone forever, but they have now found that peat can actually re-freeze it through this ‘cold-pump’ process.

This is why it is vital to make sure that development does not disrupt these ecosystems, says Kopansky. “They’re like a giant sponge,” she says. “If you cut them in half, it collapses, and you lose that really amazing function that they have.” But disturbances in such remote areas are not always monitored, and decisions about the landscapes are not necessarily made in holistic ways, she adds. What’s more, the rising demand for natural resources and increased accessibility to frozen regions due to warming might lead to increased industrial and infrastructure activity in these areas, escalating disturbance to peatlands and permafrost.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean we should cordon off these areas from any kind of human interaction, notes Kopansky. “There are a lot of ways that people have been using peatlands without disturbing them.” So recognizing the rights of indigenous peoples to manage these landscapes is an important piece of the puzzle.

In Canada, the Ontario Far North Act recognizes the significant role of First Nations in protecting ecosystems like permafrost peatlands and promoting land-use planning that helps to up their sequestration potential even further.

Yannick Beaudoin, director general of the Ontario/Northern Canada chapter of the Canadian environmental research non-profit David Suzuki Foundation, agrees. “It really is about recognizing the long-term knowledge of stewardship that Indigenous groups have,” he says. “There is 10,000 years of knowledge on how to adapt to climate change because they’ve had to do it before – but it’s still not fully recognized by Western science.”

Some of the regional governments with which Beaudoin works are beginning to take this experience into account. “There’s more recognition of where sound knowledge can come from, and rather than impose a centralized approach, there’s been much more conversation,” he says, “although there is still a lot left to be done.”

However, it is also important to recognize that the current rate and extent of climate change is unprecedented, and Indigenous perspectives and Western science need to work together. “The Arctic is changing so quickly now,” says Beaudoin, “so on its own, First Nation knowledge is no longer necessarily able to meet that rapid rate of adaptation. That’s why these communities do also want to bridge to the latest available knowledge and science and the support that can come into play.”

In March of this year, the UN Environment Assembly passed a resolution that saw countries, stakeholders and partners commit to work toward the conservation and sustainable management of peatlands. Kopansky hopes that the global community of landscape management policymakers and practitioners will help to maintain momentum around the protection of these unique and often-ignored ecosystems.

Taking an interdisciplinary, multi-stakeholder landscape approach to peatland conservation will be critical, says Kopansky. “I think using a landscape approach for peatlands works phenomenally because we really can’t look at this ecosystem in bits. It can’t be divided by borders, fences or roads – it needs to be taken as a whole,” she says. “We need all of the partners at the table really trying to work together.”

It’s complex work, but the rewards of quick action would be significant, Kopansky says. “Peatlands cover only 3 percent of the Earth’s surface, but they’re responsible for 5 to 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions when they’re disturbed,” she adds. “So really this is a very low-hanging fruit. If we concentrated restoration, conservation and protection efforts on peatlands, we would have a significant impact in lowering emissions immediately.”

“But we have to do it now.”

Header Image Credit: The permafrost peatlands of Cape Bolvansky, Russia. Hans Joosten