Written by: Dilrukshi Handunnetti

Sri Lanka’s southern coastline is dotted with popular resorts and beaches, but this once pristine landscape hasn’t been spared by the global plastic waste crisis, a study finds.

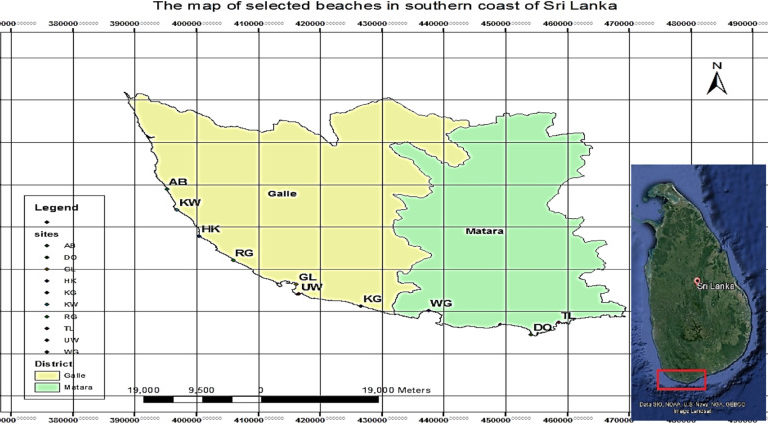

The authors of the paper, published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, studied 10 locations along a 91-kilometer (57-mile) stretch of the Indian Ocean island’s southern coast to assess the magnitude of the problem.

They found that 60 percent of the sand samples and 70 percent of the surface water samples they collected contained an abundance of microplastics, or MPs, compounding the environmental pressure on a coastline ravaged by the 2004 tsunami and constantly battling against coastal erosion.

The problem is just the tip of the iceberg, says lead author J. Bimali Koongolla, a marine scientist at the University of Ruhuna in Sri Lanka.

“Microplastic waste is becoming a serious environmental problem in Sri Lanka, once considered an island state with unblemished pristine beaches,” she told Mongabay. “The seas are getting contaminated, and beyond environmental, this poses a severe health hazard as it impacts food chains.”

She attributed the rising levels of microplastics in the seas and beaches to be poor waste management and an inability to break away from age-old littering practices.

“The use of plastics is increasing non-biodegradable waste production. These plastics eventually get washed into the seas, polluting the very environment [local communities] depend on for sustenance,” Koongolla said.

Recreational beaches under threat

The sites worst affected by plastic pollution were Dondra, Weligama and Ambalangoda, all in Southern province, due to significant recreational activity as well as fishing.

While recreational beaches had high levels of MPs, more remote beaches and fishing ports also exhibited large amounts of microplastic pollution as well as plastic debris, the researchers found.

The size of MPs in surface water and beaches ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 millimeters (0.06 to 0.1 inches) and 3 to 4.5 millimeters (0.12 to 0.18 inches), respectively. Most were identified as polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), with some polystyrene (PS) foam being also being discovered at a few sites.

Researchers found an overall higher abundance of MPs on the beaches than in the waters, while samples from the ports indicated higher levels of MP pollution in the surface water.

When sediments were analyzed, the popular and congested recreational beaches appeared to have more microplastic litter. The busy public beach of Weligama was the most polluted by count (157 microplastic items per square meter) as well as weight (5.98 grams per square meter).

Though busy recreational beaches like Weligama are cleaned routinely, the process only removes the larger debris and risks burying microplastics even deeper in the sand.

The fishing ports in Dondra and Ambalangoda also showed high concentration of MPs by count and weight in the surface water. “This is due to high levels of gear handling and other activities,” Koongolla said.

She added that at the three sites classified as remote beaches, there was little or no polystyrene found, and only one of them yielded high counts of MPs in the sand. “This is largely due to storm activity depositing water-borne and land-based debris via runoff,” Koongolla said.

Role of rivers

Koongolla said that while tourism had flourished in Sri Lanka’s south, good waste management practices have not been introduced.

“South has traditionally had a high density of tourist activity, along its coast,” she said. “While we cannot confirm if any MP samples we collected originated in the sea from fisheries or commercial vessels or on land, we can confirm that these beaches are used heavily due to increased tourist activity and tend to leave a lot of visible plastic debris.”

Researchers also say there is a dire need to identify the sources of microplastic pollution. This includes determining the role of rivers in transporting MPs into the ocean. “Once we narrow down the localities that are particularly polluting, it is easier to introduce waste management initiatives and to take other preventive action. These can vary from restriction of single-use plastics to having better recycling centers,” Koongolla said.

The study came out just before findings from a 2018 survey — commissioned by the National Aquatic Resources Agency (NARA) and supported by Norway’s Institute of Marine Research (IMR) and carried out on the Norwegian research vessel Fridtjof Nansen — were published in January.

The survey, the first of its kind in 40 years, found that nearly four-fifths of small pieces of the plastic waste in Sri Lanka’s territorial waters arrived via rivers and canals, said Terney Pradeep Kumara, general manager of the Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA).

“This means only about one fifth of waste is sea-originated microsplastic wastage, caused by fishermen dumping plastic in mid-sea and oil spills from ships,” said Kumara, also a co-author of the southern coastal study.

Following the Nansen survey, Kumara called for collective and effective waste management mechanisms and stricter laws to prevent extensive marine pollution.

Further studies needed

The team of researchers point to the absence of sufficient coastal studies as a key reason for selecting the south, a top tourist destination.

So far, only two studies have looked at microplastic pollution in the island’s coastal regions. A 2018 study looked at three beaches in Western province, while a 2016 study focused on the north coast.

Koongolla said this new study offers only a glimpse of the microplastic problem in Sri Lanka. Ideally, she said, research should be conducted over different seasons and across several years. Sampling volumes should also be much larger to improve the quality of the data, she said.

Header Image Caption & Credit: a harbor in southern Sri Lanka studded with microplastics, an emerging environmental problem in the Indian Ocean island, once known for its pristine beaches, courtesy of J. Bimali Koongolla.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.org