Written by: Maria Salazar

Under the sea, jutting into the Pacific from the southern Peruvian department of Ica, rises a mountain range called Dorsal de Nasca. The 93 submarine mountains harbor more than 1,100 species, many of them endemic, and a section of the range has become the latest marine protected area proposed by the Peruvian government.

The country’s minister of the environment, Fabiola Muñoz, made a firm promise to designate more than 50,000 square kilometers (19,300 square miles) of this underwater mountain range as a protected natural area during the III Congress of Protected Natural Areas of Latin America and the Caribbean, held in Lima in mid-October 2019. The protected area, called Dorsal de Nasca National Reserve, would be located 140 km (76 nautical miles) off the Peruvian coast.

According to the proposed marine reserve’s constitutional documents, Dorsal de Nasca would allow Peru to jump from protecting just 0.48% of its territorial waters to 6.5%, carrying the country closer to its commitment to bring at least 10% of its ocean under some form of protection.

Protection would prevent the government from granting any marine concessions within the area. Trawling by large fishing vessels, which can damage underwater habitat, is already prohibited, but fishing by other methods would continue.

An underwater mountain range

Dorsal de Nasca will be the largest protected area and the first underwater mountain range to be protected in Peru, according to Alicia Kuroiwa, director of habitats and endangered species for the international marine conservation NGO Oceana in Peru. Kuroiwa was part of the team that prepared the reserve’s constitutional documents.

She drew a parallel between the Dorsal de Nasca and the Andes mountain ranges, saying that both act as highways for the movement of species. “There is a sea lion that only lives on Easter Island, it never reaches the coast of Chile, but does reach Punta Marcona in Peru, because the mountain range helps to guide it to our coasts,” Kuroiwa told Mongabay Latam.

Southern species such as southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina) and emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) have also appeared in Punta Marcona, located about 480 km (300 mi) northwest of the Chilean border. “These animals travel from south to north and when they find the mountain range they follow this path,” Kuroiwa said.

The Dorsal de Nasca ridge butts into another ridge, called Dorsal de Salas y Gómez. Together the two chains of volcanic underwater mountains extend for 2,900 km (1,570 nmi) off the coasts of Peru and Chile. Formed over approximately 30 million years, the mountains reach a depth of 4,000 meters (more than 13,000 feet).

Yuri Hooker, a biologist at the Marine Biology Laboratory of Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, said studies are still needed to really understand this marine area delineated by the mountains. “Potentially the area may have high biodiversity, but the truth is that not much is known about this place,” Hooker said.

Hooker said he believes it is necessary to create the Dorsal de Nasca reserve. However, he pointed out that the government has yet to protect some better-studied marine areas known to have high biodiversity and endemism. As a prime example he mentioned Peru’s northern waters, where the Grau Tropical Marine Reserve, four areas totalling almost 1,160 km2 (450 mi2) was first proposed back in 2011. “More than 70% of the biodiversity of the entire Peruvian sea is concentrated on a small coastline of 150 kilometers,” or 80 miles, said Hooker.

Hooker also mentioned other priority ecosystems, including a ridge off northern Peru and coastal areas of the department of Arequipa, in southern Peru. “Ideally, many marine protected areas will be created, including the Dorsal de Nasca and those mentioned above, but what should not happen is to ignore areas that are probably biodiverse but more complex to manage only to establish other remote, deep and inaccessible areas for the sole purpose of achieving a percentage of protected oceans,” he said.

The fear is that the establishment of the Grau Tropical Marine Reserve, which faces opposition from the oil and gas sector, will be put to one side because of existing oil concessions in the area.

“It’s a political decision,” Kuroiwa said about the delays in establishing the Grau Tropical Marine Reserve. “It has been before the Council of Ministers for two years and so far it has not been approved.”

A reserve on the way

According to the Dorsal de Nasca reserve’s constitutional documents, scientists have documented 1,116 species around the Dorsal de Nasca and Dorsal de Salas y Gómez ridges. Thirty of them are regarded as being in danger of or vulnerable to extinction, such as the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). An estimated 41% of the area’s fish species and 46% of the invertebrates are endemic. It is home to deep-sea species such as cold-water corals and cod, that are considered vulnerable. Some migratory species like the humpback whale pass through the area.

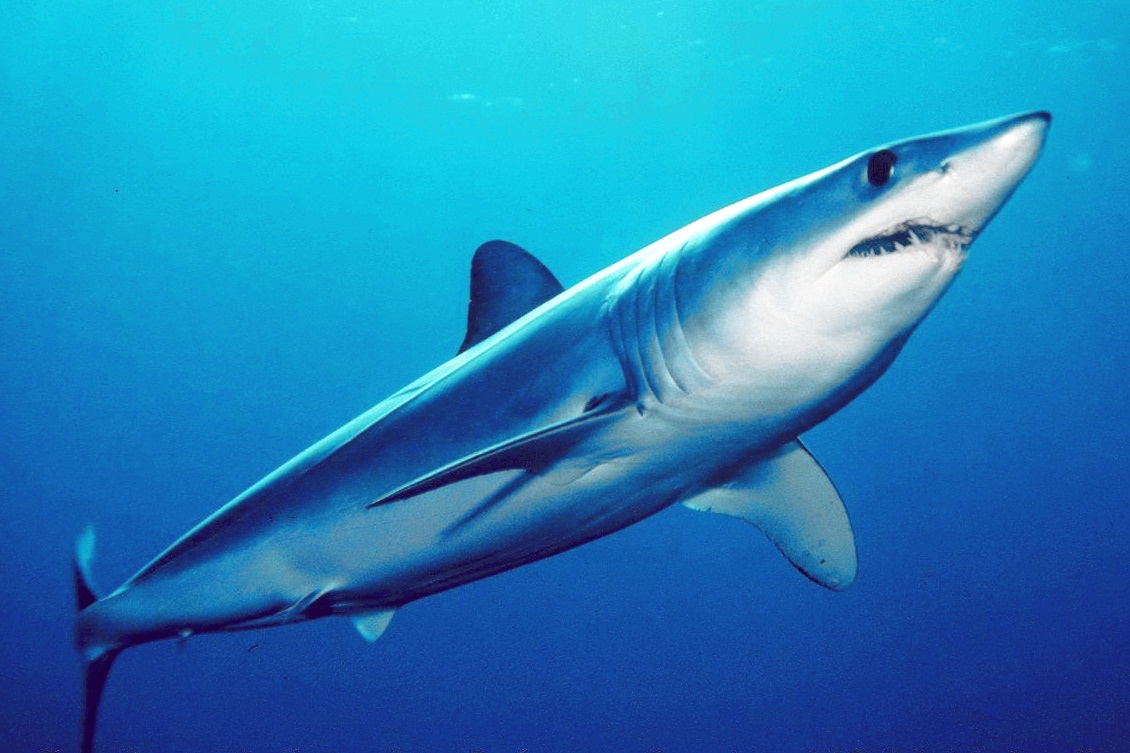

Commercial species also pass through the area: squid, deep-sea cod, perico and sharks. According to the constitutional documents, 12 commercially important species are fished in the area.

Pedro Gamboa, head of the National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP), said the proposal for the Dorsal de Nasca reserve’s establishment was developed with the intention of representing as many of Peru’s marine ecosystems as possible.

The process of establishing the reserve is in the consultation stage, and all the stakeholders are involved, according to Gamboa. Once a consensus among the sectors has been achieved, it will be submitted for approval to the Council of Ministers, the Peruvian cabinet. “The goal is to have the two reserves approved simultaneously,” he said, referring to the Dorsal de Nasca National Reserve and Grau Tropical Marine Reserve.

Gamboa acknowledged that the oil concessions in the north are a stumbling block for the Grau Tropical Marine Reserve. But he said he hopes this impasse will be overcome and the Peruvian government will be able to fulfill the commitment the environment minister made in October, which was to establish both reserves by 2021.

Joanna Alfaro, a marine biologist and president of the Peruvian nonprofit Pro Delphinus, who contributed to the Dorsal de Nasca proposal, said the main stakeholders now being consulted are the fishers who visit the area to catch commercially important species such as squid and perico. “There is industrial and artisanal fishing activity,” she said.

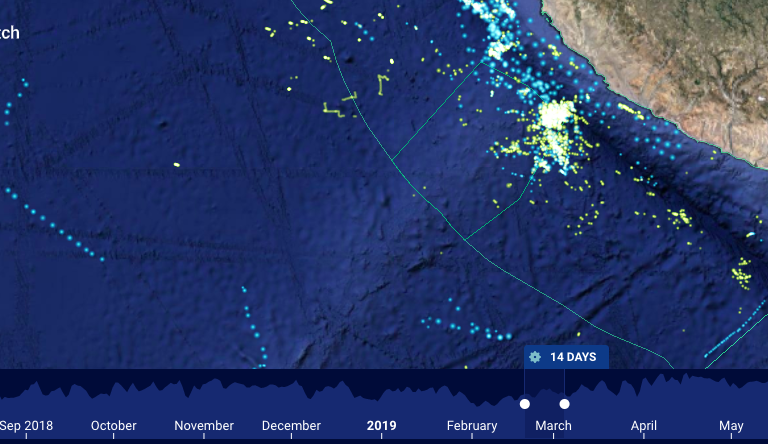

Image courtesy of Global Fishing Watch.

Illegal fishing is the main threat to the area, according to Kuroiwa of Oceana. Trawling is not permitted there, but large vessels are able to enter to carry out this activity in an unauthorized manner.

One of the actions to protect the reserve will be satellite monitoring through Global Fishing Watch, a service that allows real-time monitoring of fishing vessels.

Header Image Caption & Credit: The shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) is one of 12 commecially important species in the proposed Dorsal de Nasca reserve. Image by Mark Conlin/NOAA SWFSC Large Pelagics Program

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.