Written by: Derek Armitage, Ella-Kari Muhl, Merle Sowman, Philile Mbatha, and Wayne Stanley Rice

A little more than a year ago, the Haida Nation released the Land-Sea-People plan to manage Gwaii Haanas, off the coast of northern British Columbia, “from mountaintop to seafloor as a single, interconnected ecosystem.”

It’s an innovative conservation effort that demonstrates how the Haida Nation and Canada’s federal government can achieve biodiversity targets, protect the rights of Indigenous people and encourage collaboration among communities, governments and society. And it’s an example of what we need more of to meet conservation objectives in the coming decade.

The Aichi Targets for biodiversity conservation date back to 2010 and provided nations with the goalposts for the protection of species and habitats. Each of the 194 signatories to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) was expected to meet all 20 targets by December 2020 — ranging from preventing the extinction of threatened species to expanding protected area coverage. But few of the targets have been adequately met.

Now that 2020 deadline has almost passed, and a global population of 7.8 billion people is demanding innovative conservation strategies — strategies that reflect ecological and political realities.

In January, the CBD released the zero draft of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. This framework will provide a global pathway to conservation action. But what if we aren’t on the right path?

Between 2010 and 2020, the portion of land under protection increased to 15 from nine percent, but biodiversity loss continues at high rates. Clearly, conservation is as much about the critical role of communities as custodians of biodiversity as it is about creating people-free zones.

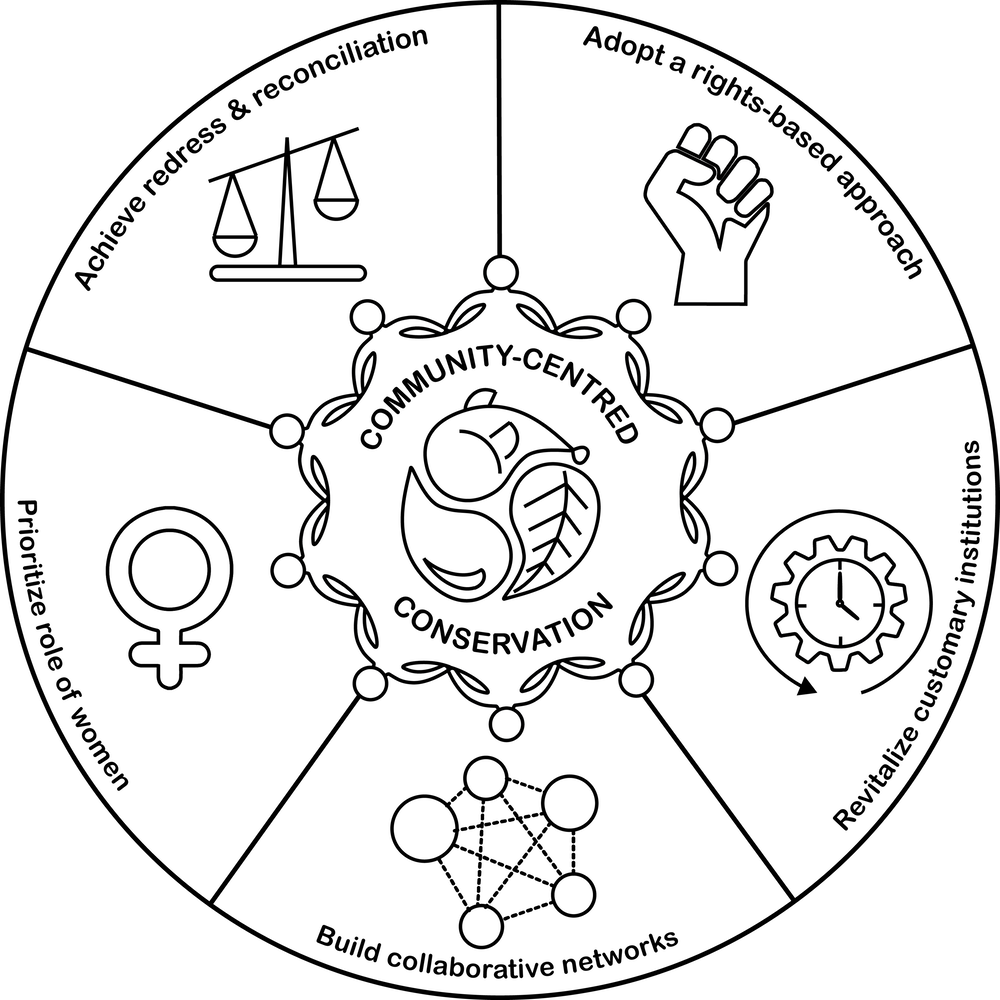

Community-centred conservation

Conservation enclosures, which restrict the access of communities to nature, are only one strategy to protect biodiversity. There is ample evidence that Indigenous-controlled territories are also crucial to sustain habitats rich in biodiversity and the cultural knowledge that comes with those environments.

For example, the recently established Edéhzhíe Indigenous protected area in the Northwest Territories covers 14,218 square kilometres. The area will conserve nationally significant habitat for caribou and it will be jointly managed by the Dehcho First Nations and the Government of Canada.

Conservation that centres on the people that know and depend on their environment, including forests, lakes and wildlife, can showcase the leadership of local and Indigenous communities in protecting biodiversity and help achieve global targets. The rights of local communities to make decisions about their own resources — fish and forests, for example — must be recognized and supported through clear laws and regulations, which have not been a focus of the Aichi Targets.

Our research identifies five ways governments and conservation partners can support community-centred conservation for the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. These principles for action emerge from lessons learned during our participation in a large community conservation research network, and our experience with conservation initiatives in Canada, South Africa and a wide range of other countries.

1. Build trust-based networks of people to collaborate for conservation

When governments, communities, environmental NGOs or other partners work together, they have a positive influence on conservation outcomes because levels of trust increase. For example, increased social engagement and the sharing of different types and sources of knowledge has been shown to strengthen relationships and networks of collaboration.

More participation by community members and their representation in decision processes, greater compliance and strong local leadership are all linked to better ecological and biodiversity outcomes. But networks that are based on trust need support from external partners and should reflect community level priorities, as has been the case in many of the marine conservation efforts in the Coral Triangle in southeast Asia.

2. Promote equity and gender equality

Various international human rights agreements protect equity and promote equality for different groups, such as women or vulnerable communities, in terms of access to natural resources. However, structural barriers, including a lack of access to markets or cultural stigma remain in place and undermine efforts of community members — particularly women — to protect the biodiversity they depend upon.

Women, must be ensured opportunities (and be fully supported) to develop and apply their own solutions to the conservation dilemmas they face. This requires a greater understanding of the conservation concerns of women and recognition of the value they add to conservation decision making.

3. Support reconciliation and redress

Past social injustice in conservation, such as land grabs and strict conservation enclosures, is characterized by forced displacement and exclusion. These experiences have exacerbated conflicts within and among local communities, and negatively influenced support for conservation initiatives.

Strategies to promote reconciliation and redress for past injustices must be placed firmly on the conservation agenda across all levels — international, regional and local. This means recognition of local and Indigenous land and resource rights must be prioritized.

(CC BY 4.0)

4. Adopt a ‘rights-based’ approach

Social justice is crucial to the success of conservation efforts in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. It is not getting the attention it deserves.

Rights-based approaches in conservation, like the right to information or the right to security and freedom from discrimination, are becoming more widely promoted as a way forward for equity and reconciliation in conservation initiatives. A rights-based approach means much greater transparency about who gets access to critical resources and habitats, and who has the ability to participate meaningfully in decision‐making.

Transitioning to rights-based approaches is particularly important for local and Indigenous communities because it enables local stewardship and improves conservation outcomes. There are examples of progress, but this transition requires a commitment to power sharing and increased collaboration from government and private actors, which is still rare.

5. Respect and revitalize local rules for decision making

The importance of long-standing local rules that determine when, where and how much of a natural resource is used is now widely acknowledged. In practice however, greater respect for local rules or customary systems of resource use is still needed. Many of these long-standing rules also require revitalization and support from partners.

Efforts to revitalize Indigenous languages are one way forward. So are initiatives to rebuild local rule-making systems, like the practice of sasi laut, a form of community-based coastal resource management in parts of Indonesia. This focus on customary rules also means that alignment with rights-based conservation approaches are crucial, along with a focus on reconciliation as a pathway to conservation in the post-2020 framework.

Looking ahead post-2020

The post-2020 global biodiversity framework can yield much-needed ecological and social outcomes, but to do so we must reconcile past injustices associated with conservation action. Ultimately, communities are at the heart of global efforts to sustain a healthy world where nature and human well-being are linked. In the era [of] climate change and the opportunity to reimagine our global economic model, a renewed focus on community may be just what we need.

Header Image: Quang Nguyen Vinh/Pexels