Written by: Kimberly White

Restoring one of the world’s rarest habitats could prevent the release of 394 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Peatlands are a type of wetland created when decaying vegetation and organic materials are waterlogged and accumulated for thousands of years. Peatland landscapes can be found all around the world from Scotland to Indonesia to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

While they can be found in nearly every country, peatlands only cover 3 percent of land globally. The largest terrestrial store of carbon on the planet, peatlands store more carbon than the world’s forests, housing over 550 gigatonnes of carbon.

However, while peatlands are quite effective at carbon storage, the landscape can quickly be turned into a carbon source.

When drained and degraded, peatlands release greenhouse gases and are highly susceptible to fires. Primarily drained for cropping, grazing, forestry, and resource extraction, the world has lost approximately 15 percent of its peatlands. Degraded peatlands account for 6 percent of anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions.

In 2015, fires ravaged Indonesia’s forests and peatlands, causing the country’s emissions to rise astronomically. The World Bank estimated that the fires cost Indonesia $16 billion in economic losses. The fires and resulting haze led to the premature deaths of 100,000 people.

Credit: Aulia Erlangga/CIFOR (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Peatland fires can occur for various reasons. Fire is often used to stake claims to land during disputes between small farmers and large corporations. Fire is also frequently used to clear land for development and agriculture. Following the 2015 fires, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo made a moratorium on the draining and conversion of unopened peatland.

Historically, palm oil has been a significant driver of peatland conversion. Widespread development of palm oil plantations has threatened endangered species. Peatlands are incredibly biodiverse, providing refuge for a wide range of tropical plants and animals, including elephants, orangutans, and tigers.

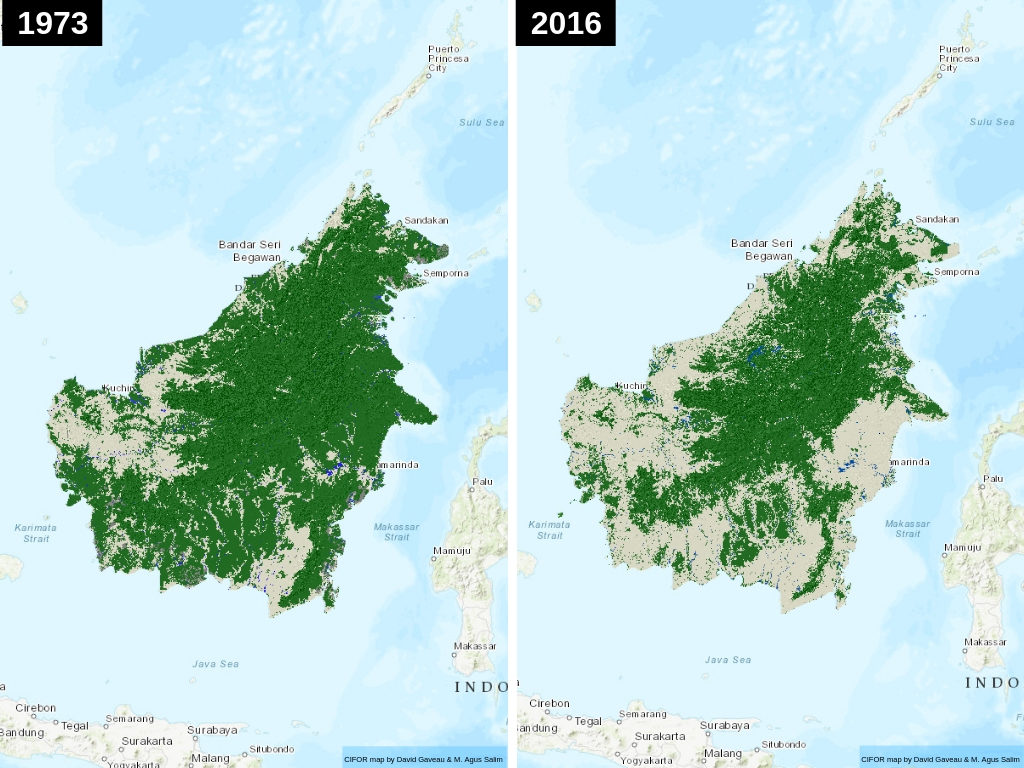

Borneo, the world’s third-largest island, has lost more native rainforest than anywhere else on the planet. Once covered in tropical rainforests and peat swamp forests, land development and clearing for palm oil and pulpwood plantations has drastically reduced forest cover.

Credit: David Gaveau & M. Agus Salim /Borneo Atlas

A 2018 study found that 100,000 Bornean orangutans were lost between 1999 and 2015 due to deforestation and habit loss. The population decline of Sumatran elephants, Sumatran rhinos, Sumatran tigers, and Bornean pygmy elephants has been linked to habitat loss from palm oil plantations.

Credit: Faizal Abdul Aziz/CIFOR (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Importance of conservation and restoration

The conservation and restoration of these rare habitats would safeguard biodiversity, provide positive impacts for human health, and aid in climate change mitigation.

Peatland protection would improve air quality, reduce fire emissions, and, as a result, reduce occurrences of toxic haze. A recent study found that peatland protection would prevent approximately 24,000 deaths per year across Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Peatland protection in the region would “reduce fire emissions and avert 66 percent of excess mortality.”

“Degraded peatlands are subject to severe fires,” said Himlal Baral, Senior Scientist at CIFOR. “Restoration of degraded peatlands with rewetting by blocking canals is one of the most effective strategies to preventing fire and associated emissions reduction.”

Peatlands are vital to climate change mitigation. These biodiverse habitats are effective carbon sinks and can provide long-term carbon storage.

Peatland conservation and restoration has to become a key priority to keep the global temperature rise below 2°C. Scientists estimate that peatland restoration could prevent the release of approximately 394 million tonnes of carbon dioxide each year.

In March 2020, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the UN (FAO) released Peatland Mapping and Monitoring, a guideline for countries to reduce peatland degradation through mapping and monitoring.

“Mapping peatlands to know their location, extent and greenhouse gas emissions potential, can help countries to plan and better manage their land, water and biodiversity, mitigating climate change and adapting to it more effectively,” said Maria Nuutinen, FAO’s lead peatlands expert with the Forestry Department and co-author of the publication.

Peatlands are often difficult to recognize, making mapping a challenge. The world’s largest tropical peatland, the Cuvette Centrale, was unknown until 2012. This biodiverse peatland complex is as large as the United Kingdom. Scientists estimate that the Cuvette Centrale holds the equivalent of two decades of U.S. fossil fuel emissions.

“Peatland mapping and monitoring are both highly complex endeavours, but are key to understanding the real extent and location of these huge carbon stores and guide the course of action for ecosystem conservation and restoration during this decade and beyond,” said Mette Wilkie, FAO’s Director of Forestry Policy and Resources Division.

Header Image Credit: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)