Written by: Jeff Berardelli

Alarming heat scorched Siberia on Saturday as the small town of Verkhoyansk (67.5°N latitude) reached 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit, 32 degrees above the normal high temperature. If verified, this is likely the hottest temperature ever recorded in Siberia and also the hottest temperature ever recorded north of the Arctic Circle, which begins at 66.5°N.

The town is 3,000 miles east of Moscow and further north than even Fairbanks, Alaska. On Friday, the city of Caribou, Maine, tied an all-time record at 96 degrees Fahrenheit and was once again well into the 90s on Saturday. To put this into perspective, the city of Miami, Florida, has only reached 100 degrees one time since the city began keeping temperature records in 1896.

Verkhoyansk is typically one of the coldest spots on Earth. This past November, the area reached nearly 60 degrees Fahrenheit below zero, one of the first spots to drop that low in the winter of 2019-2020. The scene below is certainly more characteristic of eastern Siberia.

Reaching 100 degrees in or near the Arctic is almost unheard of. Although the reading is questionable, back in 1915 the town of Fort Yukon, Alaska, not quite as far north as Verkhoyansk, is reported to have reached near 100 degrees. And in 2010 a town a few miles south of the Arctic circle in Russia reached 100.

As a result of the hot-dry conditions right now, numerous fires rage nearby, and smoke is visible for thousands of miles on satellite images.

This heat is not an isolated occurrence. Parts of Siberia have been sizzling for weeks and running remarkably above normal since January. May featured astonishing warmth in western Siberia, where some locales were 18 degrees Fahrenheit above normal, not just for a day, but for the month. As a whole, western Siberia averaged 10 degrees above normal for May, obliterating anything previously experienced.

On May 23, the Siberian town of Khatanga, far north of the Arctic Circle, hit 78 degrees Fahrenheit. This was 46 degrees above normal and shattered the previous record by a virtually unheard-of 22 degrees. On June 9, Nizhnyaya Pesha, an area 900 miles northeast of Moscow, near the Arctic Ocean’s Barents Sea, hit a sweltering 86 degrees Fahrenheit, a staggering 30 degrees above normal.

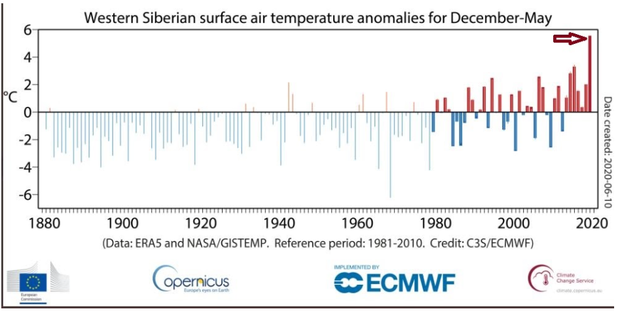

What’s perhaps even more impressive is that this relative warmth has persisted since December, with average temperatures in western Siberia 10 degrees Fahrenheit above normal — doubling the previous departure from average in 2016.

The average heat across Russia from January to May is so remarkable that it matches what’s projected to be normal by the year 2100 if current trends in heat-trapping carbon emissions continue. In the image below, the data point for 2020 is almost off the charts, and matches what climate models expect to be typical many decades from now.

The extreme events of recent years are due to a combination of natural weather patterns and human-caused climate change. The weather pattern giving rise to this heat wave is an incredibly stubborn ridge of high pressure; a dome of heat which extends vertically upward through the atmosphere. The sweltering heat is forecast to remain in place for at least the next week, catapulting temperatures easily into the 90s in eastern Siberia.

But this heat wave can not be viewed as an isolated weather pattern. Last summer, the town of Markusvinsa, a village in northern Sweden on the southern edge of the Arctic Circle, hit 94.6°F. Warming and drying of the landscape is leading to unprecedented Arctic fires, with the summer of 2019 being the worst fire season on record.

Due to heat trapping greenhouse gases that result from the burning of fossil fuels and feedback loops, the Arctic is warming at more than two times the average rate of the globe. This phenomenon is known as Arctic Amplification, which is leading to the decline of sea ice, and in some cases snow cover, due to rapidly warming temperatures.

Over the past four decades, sea ice volume has decreased by 50 percent. The lack of white ice, and corresponding increase in dark ocean and land areas, means less light is reflected and more is absorbed, creating a feedback loop and heating the area disproportionately.

As the average climate continues to heat up, extremes like the current heat wave will become more frequent and intensify. Scientists say there is only one way to dampen the impact of climate change and that is to stop burning fossil fuels.

This story originally appeared in CBS News and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.