Written by: David Elliott

The world’s largest all-electric plane has completed its maiden voyage, flying for 30 minutes in the skies above the US state of Washington.

Its safe landing in Moses Lake, about 300km southeast of Seattle, is a milestone in a dream that’s been floating about since the late 1800s – air travel powered by electricity.

From two French army officers strapping batteries to an airship in 1884 to the prototypes, demonstrators and leisure craft that have been built since, it’s been a long journey.

Is this latest breakthrough a sign that the long-predicted electric revolution is finally coming in to land?

No emissions

Perhaps not quite, although the modified Cessna Grand Caravan that completed the flight is “another step on the road” to operating electric aircraft on short routes, according to Roei Ganzarski, CEO of magniX, which developed the plane’s 750-horsepower propulsion system.

The nine-seater eCaravan, which magniX developed with aerospace firm AeroTEC, used less than $6 worth of electricity for its 160km flight. Compare that to a conventional combustion engine, which would have used around $300 to $400 worth of fuel for the same trip.

MagniX says 5% of global flights are under this distance.

Electric motors are also quieter and need less maintenance than fossil fuel engines. They’re more efficient, too – turning 90% or more of their power into “useful work”, according to NASA. And, when that power is generated cleanly, there are no carbon emissions.

MagniX says retrofitting an existing plane like the Grand Caravan will help speed up the certification process in a heavily regulated industry, and it hopes the aircraft will be in commercial service by the end of 2021.

But there’s still one major obstacle to electric propulsion being adopted for longer journeys – batteries.

A long haul

Due to the low energy density of current battery technology, we’ll likely have quite a wait to see an all-electric long-haul flight.

A study in the journal Nature Energy estimates that the top lithium-ion batteries have a specific energy of about 250 watt-hours per kilogram. But to compete on routes of more than 1,000km in an airliner the size of a Boeing 737, a specific energy of 800 watt-hours per kilogram would be needed.

From that perspective, the report says, it is questionable whether all-electric aircraft will be capable of long-distance routes, such as the 5,500km from London to New York.

However, electric planes designed from scratch could achieve a range of about 800km with today’s batteries, Ganzarski told PV Magazine. With about 45% of flights under this distance, according to magniX, the impact of the technology could still be huge.

Rapid growth

Credit: Roland Berger

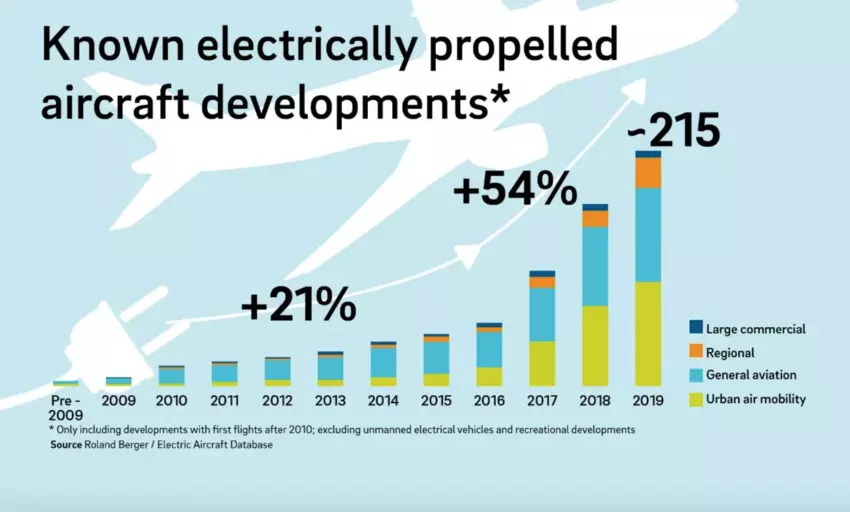

The number of electrically propelled aircraft developments grew by 30% in 2019 to more than 200 projects, according to a report from consultant Roland Berger.

That change is being driven by rapid growth in urban air mobility projects, such as urban air taxis and regional developments. MagniX, for example, has joined forces with Vancouver-based airline Harbour Air to electrify its fleet of 40 passenger seaplanes. Norway, meanwhile, has said it wants to make its short-haul flights 100% electric by 2040.

Major airlines are getting involved too, including Scandinavia’s SAS, which says it wants to work with Airbus to research hybrid and electric aircraft, and easyJet, which is developing a 186-seater electric aircraft with US start-up Wright Electric that it hopes to test in 2023.

The French government has also recently pledged €1.5 billion (US$1.7 billion) to develop a ‘carbon-neutral’ plane by 2035. The money is part of a €15 billion bailout package for the aviation industry.

Flying into the future

While the airline industry is largely grounded right now due to COVID-19, in normal times commercial aviation is responsible for about 2% of global carbon emissions. This could be set to rise – pre-pandemic projections show demand for flights doubling over the next 15-20 years.

Aviation industry body the IATA says that, rather than stopping flying altogether, the key to cutting its contribution to climate change is to make flying sustainable.

The sector has made progress in this area by improving fuel efficiency through enhanced aircraft design and operations, and has pledged to reduce net CO2 emissions to half 2005 levels by 2050.

The electrification of aviation could play an important role in reaching these goals.

Header Image Credit: magniX

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum