Written by: David Elliott

Dive beneath the brilliant blue waters surrounding Thailand’s Koh Tao island and you might come face to face with a giant sculpture of the sea goddess Mazu.

But a closer look reveals an even bigger surprise – Mazu is alive.

That’s because, as the 1,800kg centrepiece of a large artificial coral reef, she is teeming with sea life.

Built in 2018 by non-profit organization Global Coralition with the help of conservation group Eco Koh Tao, the sculpture and the 36 smaller pyramid structures that surround it hold 5,000 coral transplants. It attracts hundreds of divers a week and helps raise funds for local restoration groups, and is maintained by these divers and the local community.

Global Coralition now plans to return to the island to work with local conservation groups and scientists from Thailand’s marine resources department to build the island’s first land-based coral farm. The group is currently raising funds.

Small pieces, big impact

Angeline Chen, Executive Director of Global Coralition – who spoke recently at the World Economic Forum’s Virtual Ocean Dialogues event – is effusive about the benefits of growing coral on land and the role it could play in rebuilding damaged ocean habitats.

Coral can be grown up to 50 times faster this way, she says, using a technique called microfragmentation. This involves dividing a piece of coral into much smaller fragments, which stimulates the tissue to grow. The pieces are grown a short distance apart and – because corals are clonal animals – they fuse together when their edges meet, forming a single mass.

Combined with other scientific methods, like larval propagation and assisted evolution to increase the resilience and reproductive rate of corals, Chen believes the impact of such projects, practised all around the world,could be massive.

“With these farms, we could be growing a diverse array of resilient coral on a huge scale,” she says.

Many organizations are practising these methods, including Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida, US, and the government of Hawaii, which is out-planting 1 metre by 1 metre corals grown in one year –the largest to be grown in a land-based nursery.

Empowering communities

Driving the work of Global Coralition and organizations like it is a simple fact: coral is vital to the planet.

Coral reefs are among the most diverse ecosystems on Earth, and they support nearly 1 million species of fish, invertebrates and algae. They’re crucial to humans, too. They protect our coasts from storms and floods, and provide work, medicine and food to more than 1 billion people. In fact, coral reef ecosystems give society resources and services worth $375 billion per year, according to the United Nations.

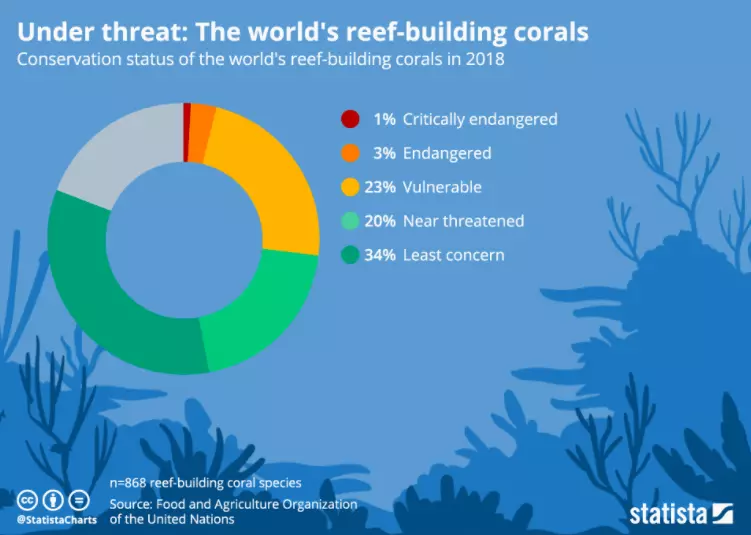

But coral faces myriad threats, including overfishing, pollution and climate change. Almost half of reef-building coral species are under threat, according to UN figures. And scientists predict we’ll lose up to 90% of all reefs in the next 20 years if something isn’t done soon.

For Chen and the Global Coralition, the answer lies in engaging and empowering local communities with the knowledge, tools and resources to reduce the local impacts of reef degradation while increasing key habitats and species.

The organization uses art, like the sculpture of Mazu, to bring people together around cultural themes that are meaningful to their communities.

It then works with parties including local officials, marine ecologists, fisherman, students and dive centres to foster the unique skills to rehabilitate their local ecology. This work in turn improves quality of life, water quality, food security, income and employment opportunities and education in the region.

Global effort

Global Coralition is currently building a marine farm in a fishing village in the Dominican Republic. It consists of an expansive underwater sculpture garden inspired by Taino wisdom, a land-based coral farm, mangrove and oyster restoration and a community education centre.

As part of this project, Chen says, it used the World Economic Forum’s UpLink platform to connect the community with a recycling facility that pays locals to collect trash, which can be turned into material to be sold back into the economy.

The organization wants to create 200 of these marine hubs across the globe in collaboration with local communities and governments, fishing villages, dive communities, restoration groups, hotels and local officials.

“Based on recovery rates, scientists predict we can rebuild marine life by 2050 if we can mitigate climate change, reduce local pressures and increase the abundance of our keystone habitats and species,” Chen says.

“If these methods were applied all over the world, we could scale our collective rates of restoration.”

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum