Written by: Julie Reimer

The ocean quietly unites global communities in a profound way. And yet, the ocean faces more threats today than ever before in history.

The facts and predictions are staggering. More than 25 per cent of the world’s fisheries are overfished, and most are operating at a maximum sustainable level with no room for those fisheries to expand.

The rate of ocean acidification, which happens when the ocean absorbs too much carbon, far exceeds what is natural. By the turn of the century, more than half of the world’s ocean species could face extinction.

People continue to carelessly develop and destroy the world’s biggest ecosystem. Ocean conservation is not just essential to safeguard biodiversity, but by protecting the ocean we also protect ourselves.

As the ocean deteriorates under climate change, our communities are also at risk. For some, this could mean watching special coastal places, including their homes, wash away as storms intensify. For others, this could mean losing the fish that support livelihoods.

A healthy, vibrant ocean supports healthy communities and a healthy planet. We see this connection in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal for the ocean, SDG 14: Life Below Water. SDG 14 has seven main targets that aim to “conserve and sustainably use oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.”

Protecting the world’s ocean

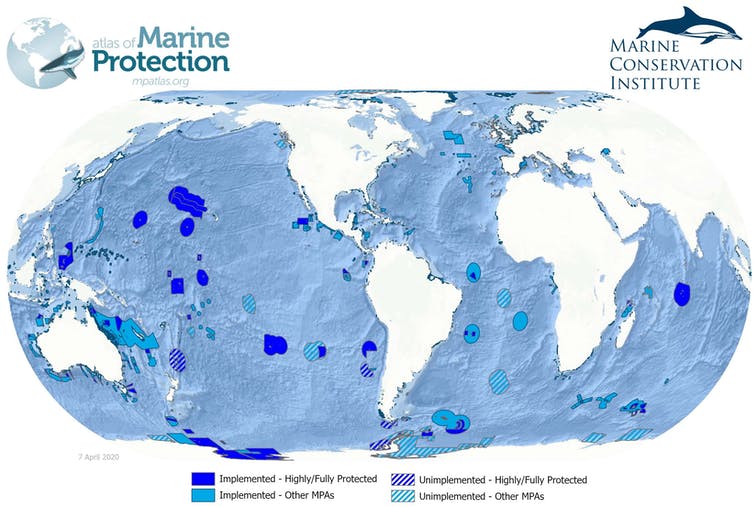

A recent study from my research shows how marine protected areas (MPAs) are an important tool for achieving ocean sustainability. Today, only 6.4 per cent of the global ocean is protected, and only 2.7 per cent of it has strong protection against harmful activities, despite scientists calling for strong protection of at least 30 per cent.

Last year, several countries joined the Global Ocean Alliance and agreed to protect 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030, a target called 30×30. If we can achieve this, we can halt biodiversity loss, ensure fish and food for all, and maintain a healthy ocean that can cope with climate change.

Not all MPAs are created equal

MPAs, in some form, have existed for decades. In the broadest sense, an MPA is an area that is managed to protect some element of ocean life by defining areas where activities are — and are not — allowed. Today they come is all sorts of shapes and sizes, but quality is just as important for MPAs as quantity.

Over the years, the pressure to expand global MPAs has led some governments to protect residual areas that are unused or have lower ecological value to avoid conflict and having to make difficult decisions. Picking the low-hanging fruit may not produce the desired outcome. Our protected areas need to be in the right places, using the right regulations to ensure that MPAs can help us with sustainability.

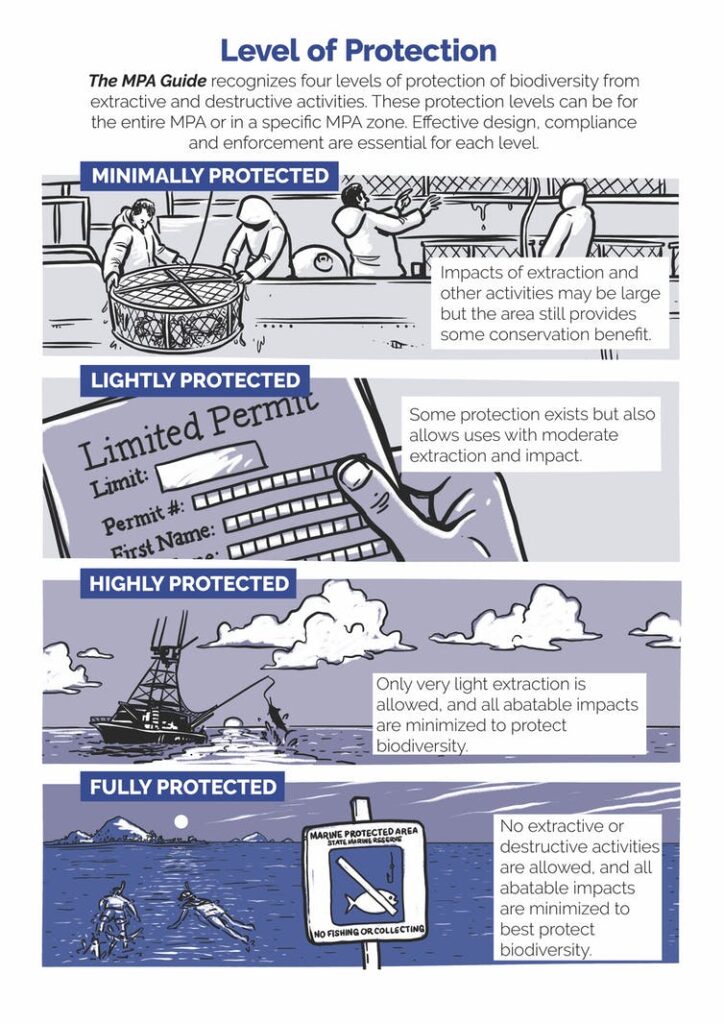

MPAs can give different levels of protection to ocean life. Protection levels can be influenced by conservation objectives, economic interests and social and cultural needs in the area.

On one end of this spectrum, MPAs can be minimally protected. In these MPAs, some extractive activities are allowed to continue, such as using fishing gear that can inflict damage on species and habitats. There may still be some conservation benefit, albeit a small one.

On the other end, MPAs can be highly or fully protected. In these MPAs, only light extraction and destructive activities are allowed (highly protected) or none at all (fully protected), giving our best protection to biodiversity.

On paper, some countries have already surpassed the 30 per cent goal, but if MPAs do not have strong regulations they are not likely to deliver the conservation benefits we need. For example, in France, 33.7 per cent of the nation’s waters are protected, but less than two per cent of this area is fully protected. The strongest MPAs have at least some portion of the area fully protected from harmful activities.

On the Atlantic coast of Canada, northern bottlenose whales swim freely in the rich waves of an underwater canyon in an MPA known as “the Gully.” As one of Canada’s oldest MPAs, this area protects hundreds of species, including whales and dolphins, fish, crabs, octopuses and other invertebrates, not to mention the highest diversity of coldwater corals in Eastern Canada.

Located in the offshore, the Gully might have little local attachment, but fishers use the area, connecting this far-off place to Canadian communities. Despite being out of sight, the Gully is not out of mind.

The Gully had been criticized in the past for lax regulations on some activities. Then, in 2019, the Canadian government banned oil and gas activities, mining and bottom trawling in all of Canada’s MPAs. Through its three management zones, including a fully protected zone from the surface to the seafloor, the Gully continues to shine as a Canadian conservation success story.

The way forward

MPAs hold the potential to help us achieve targets of SDG 14. They can help to maintain healthy ecosystems and sustainable fisheries.

They are less able to help with other SDG 14 targets, like reducing pollution or the impacts of acidification. MPA regulations end at their boundaries, but our harmful impacts do not. MPAs are one type of tool in a larger toolbox that also includes fisheries management, shipping regulations, climate change policies and more.

In an ever-changing, increasingly busy ocean, our MPAs have to work with one another and with other tools. Together, this forms the bigger picture of ocean management across habitats, ecosystems and geopolitical boundaries.

On our path to protecting a third of the ocean, we must be protecting the right areas, with strong regulations and without exacerbating injustice and inequity in the communities affected by conservation decisions. While today’s goal might say 30×30, the real ambition is to see 100 per cent of the ocean sustainably managed to ensure a prosperous future for all.