Courtesy of Landscape News

Written by: Ming Chun Tang

Wildlife and greenery aren’t Mexico City’s calling cards.

But while the world’s fifth-largest metropolis is home to more than 21 million people, it’s also grounds for nearly 4,000 species of flora and fauna, and some 15 percent of its total area consists of national parks and other protected areas.

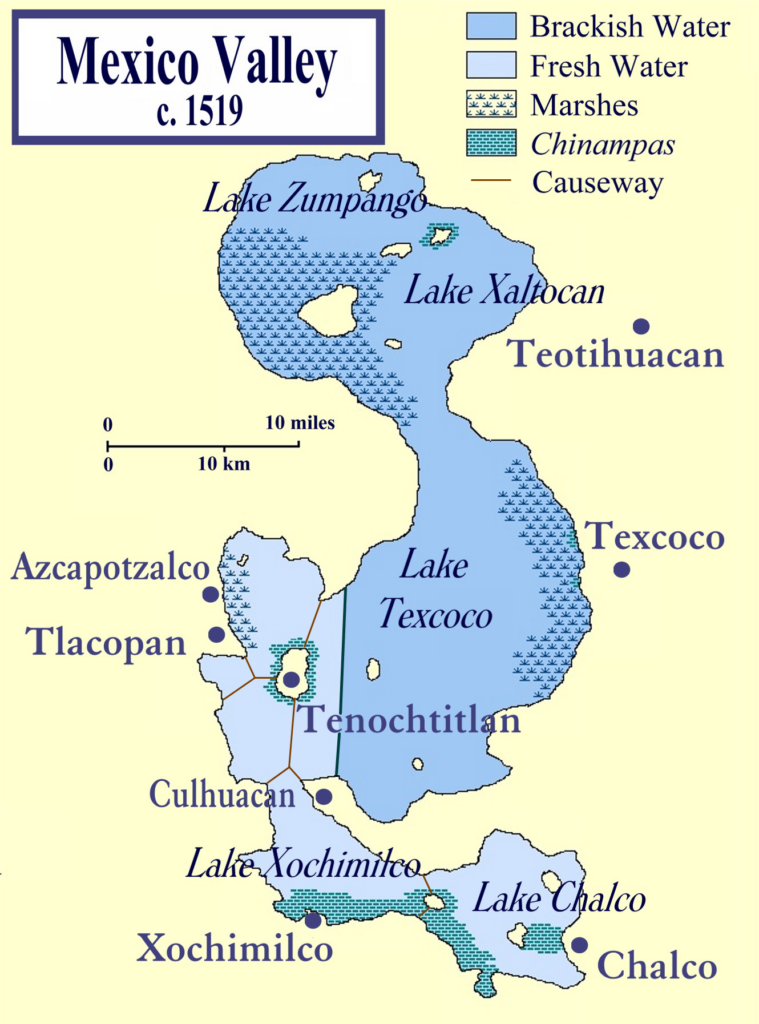

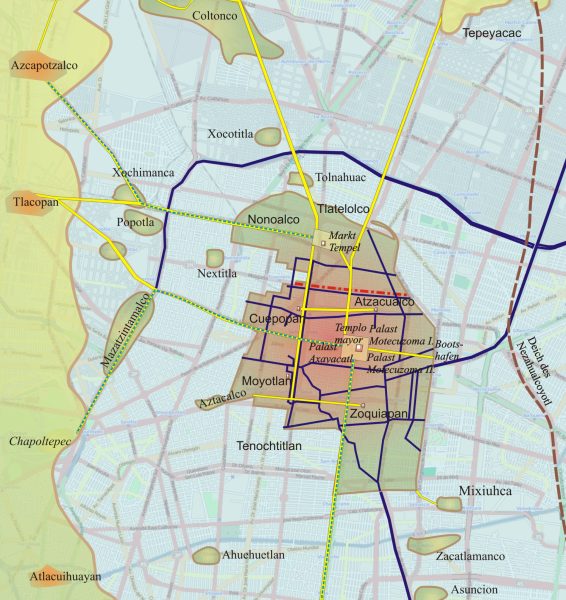

This stems from the city’s lush past. The sprawling conurbation started out as the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, built on a swampy island in Lake Texcoco, one of five interconnected lakes circled by mountains and volcanoes.

Credit: Madman2001/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

During the 15th century, the Aztecs built a sophisticated network of canals, levees and dikes to protect Tenochtitlan from the surrounding waters, as well as aqueducts to carry fresh water from springs located on the mainland. A ring of chinampas, or floating gardens, was erected around the island to feed its 200,000 inhabitants.

When the Spanish arrived in 1519, they marveled at the “Venice of Mesoamerica” before their eyes – and then proceeded to besiege and ransack the city in 1521. The colonizers then built a new capital over the ruins, before draining the lakes to prevent flooding.

Today, Mexico City is slowly sinking as the lake bed gives way, while its foundations of sand and clay leave it highly vulnerable to earthquakes. Ironically, it now grapples with water shortages even while some neighborhoods are prone to regular flooding, as its concrete and asphalt surfaces prevent underground aquifers from naturally replenishing.

Credit: HJPD/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Five centuries after abandoning the Aztec philosophy of working with nature, Mexico City is returning to its roots: in 2019, it partnered with the UNDP Biodiversity Finance (BIOFIN) initiative to ramp up its investments in conservation.

The Mexican capital currently spends 5.5 percent of its budget on biodiversity. But rather than simply increasing that spending, BIOFIN is working with the city government to make better use of its resources.

“We have to work on using our money more effectively, because we can achieve much more with the money we already have,” says Onno van den Heuvel, global manager of BIOFIN. “We also have to look at realigning our resources to achieve more. It’s a lost opportunity.”

With BIOFIN’s assistance, the city has reviewed the performance of its environmental fund and, after a competitive process, appointed a new trustee to help manage it more effectively. This has enabled the city to save around MXN 40 million (USD 2 million) in operational and transaction costs, which it is now redirecting towards conservation purposes including program design for carbon forestry of urban forests, reforestation and creation of pollinator-friendly landscapes, payments for environmental services, and capacity-building for replanting on urban grounds.

Credit: Eneas De Troya/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

This methodology is based upon BIOFIN’s guidelines as well as the SEEA methodology used by the National Statistics Institute of Mexico. The first results will be available during the first trimester of 2021.

And as the climate crisis drives increasing water shortages, the city is setting up a new agency for green investments in infrastructure, renewable energy, transportation and climate resilience, though it currently lacks the in-house expertise to evaluate potential projects.

“The agency doesn’t have a strong structure of personnel specialized in green finance,” says Daniela Torres, BIOFIN’s national coordinator for Mexico. “So we are working on defining: what is a green project, and how can the agency assess and select green projects to invest in?”

“We are selecting methodologies to evaluate these projects and to measure the impact that the agency will be creating through its investments,” she elaborates.

Despite progress at the municipal level, Mexico’s federal government is showing little interest in conservation. As the country’s environmental agency faces cutbacks, Torres believes it is more crucial than ever to appeal to private investors.

“As of today, the city is not working actively with the private and financial sectors, but we are trying to close this gap and to leverage more funds from these sources,” she says.

At the national level, BIOFIN has partnered with NUUP, an NGO that seeks to help small food producers access the market, to launch an acceleration fund that will provide USD 150,000 per year in financial and technical support to bioeconomy projects across Mexico. The fund aims to build a business case for biodiversity by catalyzing private investments in activities such as aquaculture and the production of coffee, honey and mezcal.

“The BIOFIN money will act as a trigger to leverage funds from other sources to these projects,” says Torres. “This will show that bioeconomy business models can be bankable, profitable and also environmentally sustainable.”

One project that has benefited from the fund is Cafecol, an association of coffee producers that received USD 15,000 to create a revolving fund to support farmers in the state of Veracruz in producing high-quality coffee for export to Europe. Over 100 producers stand to profit from the fund, which will enable them to sell coffee at prices around 40 percent higher than on the conventional market.

“Almost 40 percent of these producers are women, so there is a very important gender component,” Torres adds. “It will have a positive impact on deforestation, sustainable land management and community organization models.”

“If it is successful, this model will open the door to new sales channels out of Mexico, so it will be a really big milestone for bioeconomy projects here, benefiting biodiversity conservation and sustainable use as well as the local communities that depend on it.”