Written by: Izabella Teixeira and Janez Potocnik

Biodiversity is declining faster than at any other time in history, with successive major reports highlighting the huge scale of nature loss. In fact, 1 million plant and animal species are threatened with extinction, many within the next few decades. To halt and reverse these catastrophic trends, it is essential that the root drivers of biodiversity loss are addressed – especially as doing so also brings opportunities and benefits including enhancing human health and wellbeing and creating green jobs.

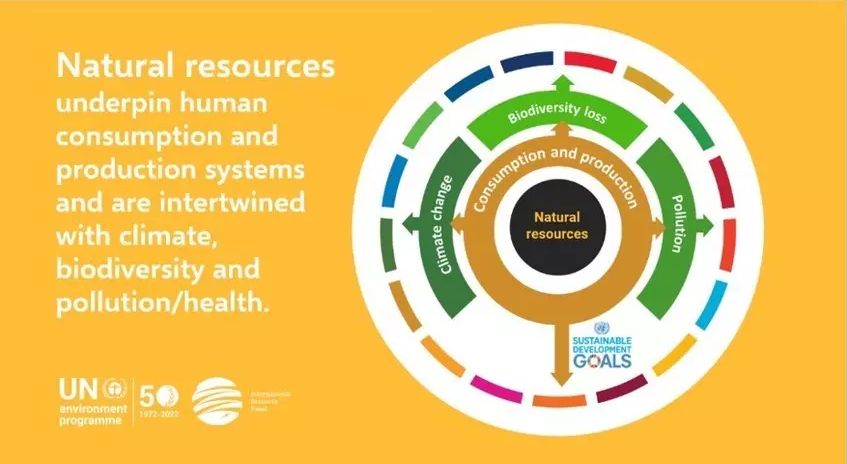

The way natural resources (land, biomass, fossil fuels, metals, minerals, and water) are managed, particularly biomass and land, has a big impact on the largest drivers of biodiversity loss: habitat destruction, overextraction, pollution, and climate change.

The International Resource Panel (IRP), hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), is focused on the relationship between natural resource use and global challenges like climate change and biodiversity loss. The IRP’s latest think-piece (or whitepaper) outlines how implementing natural resource management principles can build biodiversity, and highlights examples of how they are already delivering for nature in a whole range of different contexts.

Know your impact

Value chain transparency enables decision-makers to identify key points of intervention, where environmental impacts along the value chain caused by production and consumption can be reduced. Ideally, value chain transparency would be made a reality through strong scientific data and consistent international standards. These incentivize producers to invest in traceability – knowing that the resulting transparency would be accepted by any country they wanted to import to. Technology, policy and finance are helping to improve this transparency.

Technology: Technology is already improving transparency. For instance, chocolate producers Barry Callebaut are using satellite services to trace the origins of cocoa in chocolate supply chains. This information reduces the drivers of deforestation directly or indirectly associated with their supply of cocoa.

Policy: Governments are also driving value chain transparency: for example, the German Federal Government intends to pass a supply chain act this year, requiring companies to meet due diligence standards on human rights and environmental impacts.

Finance: Portfolios are taking an increasing interest in biodiversity but have found it difficult to invest directly because positive impacts are difficult to measure. To combat this, the Zoological Society of London has developed an online platform that details the activities of soft commodity producers, enabling proactive investors to avoid companies who have particularly damaging impacts, and to identify specific natural resource management strategies improving how activities like deforestation are managed. This tool is already being used by first-mover fund managers.

Plan together

A major contributor to the over-exploitation of resources is the fact that countries have incomplete pictures of how their natural resources are being used and how their uses impact each other. For example: a forest provides water retention and protection through its catchment for a nearby city, but it could also be a source of income for a community reliant on local timber. Without an integrated strategy, these conflicting demands will not be balanced. Having such a strategy also enables decision makers to conserve biodiversity – through early identification of biodiversity hotspots – and to achieve multiple benefits from areas of land or ocean.

Spatial planning is one way to get that full picture and craft that strategy. This approach identifies and maps areas of significance for certain species and ecosystems. Having a full picture of the resource demands makes it easier to highlight where there are trade-offs for different stakeholders and where there could be win-wins. For instance, marine protected areas increase fish populations as they provide livelihoods from sustainable tourism. In 2019, the IRP analysed over 350 integrated spatial planning initiatives from around the world, and found that a large proportion had positive impacts on agriculture, ecosystems, and livelihoods.

Case study: Integrated landscape planning in China. The intelligent eco-zoning approach taken by China is one example of how planning can help prevent biodiversity loss. For the past 10 years, China has been developing the Ecological Conservation Red Lining system. When the devastating Yangtze flood of 1998 claimed over 3,000 lives and made over 15 million people homeless, China recognized that its severity was the result of deforestation and environmental degradation. This triggered the development of technologies and scientific methods to assess biodiversity and ecosystem services, including resilience to natural disasters. Using these methods, areas are selected for protection from pressures such as industrialization and urbanization. Buy-in from local authorities has been essential for the scheme’s successful implementation; currently an area greater than France, Spain, Germany, and Italy combined is earmarked for protection based on its ecological value.

Nature-based and circular solutions

Production can be made more sustainable through the implementation of nature-based and circular economy solutions – using nature’s inherent regenerative capacity to produce materials and enhance ecosystem services simultaneously. These practices avoid ecosystem degradation, minimize waste, and assist the recovery of ecosystem functions.

Bamboo is one example of a nature-based, circular solution that can support both biodiversity and poverty alleviation. Thanks to its fast growth rate, it re-greens degraded landscapes all while providing livelihoods for farmers and for a growing secondary bamboo processing industry. This environmental and economic transformation has been demonstrated in a range of diverse locations including China, Ethiopia, India, Ghana, and Tanzania. In one Chinese municipality, the number of farmers involved in the bamboo supply chain grew 1,900 percent in just five years, bringing household income and resiliency to communities.

New ways to value nature

The intrinsic value of natural assets and the services they provide is not recognized by economic systems, and this contributes to the mismanagement of natural resources. Integrating nature into economic decision making is not the same as merely putting a price on nature; The Dasgupta Review, published earlier this year, makes the case for basing economic decisions on an inclusive measure of wealth, based on human, produced, and natural capital, thereby incorporating ecosystem extent and quality into central government decisions.

Although instruments valuing ecosystem services are still relatively rare, there are an increasing number of examples. One such initiative is the Araguaia League in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Aiming to improve the region’s environmental assets, it financially compensates activities encouraging sustainable intensification of cattle production, including conservation, and emissions reduction.

Make biodiversity targets bold and implementable

2021 has been hailed as a ‘Super Year’ for the environment, with UNFCCC COP26 in Glasgow setting new global climate goals, and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) COP15 in Kunming doing the same for biodiversity.

While biodiversity targets have been missed in the past, CBD COP15 in Kunming is a huge opportunity to harness the maximum potential of the world’s biodiversity. In Kunming, leaders need to capitalize on recent progress, which includes approval by the UN of a comprehensive framework for natural capital accounting (UN’s System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA)). National governments should commit to using this internationally-agreed statistical framework to increase the spread and depth of natural capital accounting around the world.

Other efforts have also been put into place. For instance, in September 2020, leaders from 84 countries signed the Leaders Pledge for Nature – committing to reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. They now need to make good on that pledge, by agreeing to ambitious targets in Kunming and making meaningful commitments to secure their implementation.

Also at CBD COP 15 in Kunming, efforts should be made to scale production which enhances nature, through incentives for markets, investors, and producers themselves. These should include repurposing harmful subsidies, and upscaling payments for ecosystem services schemes.

Beyond Kunming, leaders should commit to further multilateral discussions on value chain transparency standards, mapping technologies, nature-enhancing production methods, and building capacity for natural capital accounting. Only through these efforts will we have a true understanding of both our impact on biodiversity and the needs of competing stakeholders to craft a plan for shared, strategic solutions.

Header Image Credit: Kazuend/Unsplash

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum