Written by: Laurel Sutherland

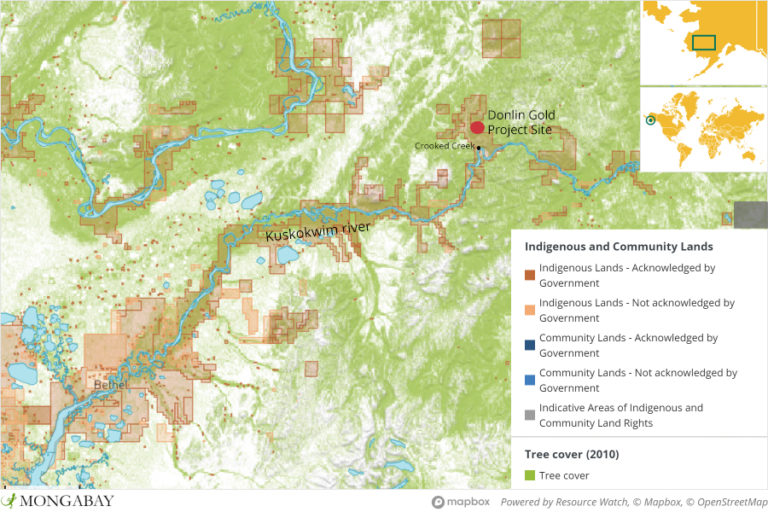

For Indigenous tribes living in Alaska’s remote Yukon-Kuskokwim region, southwest of the state, the future is bleak and uncertain. Tribal councils worry that plans to construct a 6,474-hectare (15,990 acres) open-pit gold mine near the Kuskokwim River watershed will have grave impacts on salmon habitats, their traditional ways of life and their health.

“This development could possibly destroy our livelihood, rivers and sea mammals that we depend on,” said Fred Phillips, representative of the Indigenous Village of Kwigillingok tribal council. According to him, tribes are not willing to take the risk.

The Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (YKD) drainage is part of a rich biome encompassing coastal wetlands, tundra and mountains that supports the subsistence lifestyle of three distinct Alaskan Native groups; The Yup’ik, Cup’ik and Athabascan. To access the remote region, one needs to go by boat when the Kuskokwim River is flowing, or truck, snow machine and four-wheeler when the river is frozen.

Draining into the Bering Sea to the west, the Kuskokwim River, and many of its tributaries, are designated as Essential Fish Habitat (EFH), under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act for Pacific Salmon. This is a legislation that manages marine fisheries in US waters.

The sprawling river is a vital source of food for the 38 communities that reside alongside it, serving as a running ground for the chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Given the remoteness of the region, the communities rely on subsistence fishing. Salmon makes up more than 50 percent of the tribe’s annual diet.

A mining site near salmon habitats

All salmon species usually migrate from the oceans late spring or early summer, but spawn during different months during the two seasons. While no endangered or threatened fish species are found in the drainage, the chinook salmon are of special concern in recent years due to their low population. The Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) record limited numbers of sockeye and pink salmon in Crooked Creek, one of the many tributaries of the river. This includes 12 other species of fish, including the Dolly Varden trout (Salvelinus malma), Arctic grayling (Thymallus arcticus), pike fish (Esox lucius) and two species of whitefish.

So, when Canadian-based mining companies NovaGold and Barrick Gold, through subsidiary Donlin Gold, proposed a plan to construct a massive open-pit gold mine along a tributary of the Kuskokwim about a decade ago, most affected communities disagreed. In 2019, 35 of 37 tribal governments voted in disapproval.

They feared that negative construction and mining impacts on wildlife and environment cited in the EIS would lead to disrupted access to subsistence hunting and fishing, in addition to filing fragile wetlands.

Construction plans include the mine, a 220 MW power generation plant, a tailings dam, access roads, a water treatment plant, ports, an airstrip and a steel pipeline that would be constructed to transport natural gas to the mine site. Donlin is currently conducting exploration activities.

With a mine life of 27 years, the mine is estimated to produce nearly 37 million grams (1.3 million ounces) of gold per year, making it one of the largest open pit gold mines in the world.

The mine site is located in the Crooked Creek drainage, 16 kilometers (10 miles) from an Indigenous community and the Kuskokwim River. It sits directly on several streams that feeds Crooked Creek.

The EIS states that approximately 7.5 kilometers (4.7 miles) of stream supporting fish and 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) of stream not supporting fish habitat would be lost when construction of the road and pipeline begins. The mine will contribute to increased greenhouse emissions. The exact estimate was not stated in the EIS.

There will also be a 40 percent increase in mercury deposition to surface waters near the mine, resulting in fears the mine may harm community members’ health.

“I don’t want to start a family if our cultural food will give my children cancer,” said Ananarour Sophie Swope, a youth from Bethel, one of the communities alongside the river.

Donlin stated that environmental planning and protection is a fundamental element of the project. As such the company would adhere to conditions under which the permits were issued by federal and state agencies.

“The best available technology will be utilized to meet or exceed all air and water quality standards with extensive environmental monitoring and reporting during all projects,” states Donlin Gold in its summary of the mining project.

According to Dr. David Chambers, geophysicist and founder of the Center for Science in Public Participation, a non-profit corporation that provides research and advice on mining and water quality, the consequences of this mine may be similar to that of some open mine projects around the world.

Mining activities at the current largest open pit mine, the Bingham Canyon mine in Utah, U.S, has resulted in damage to fish and wildlife habitat, extensive water pollution, and public health and safety risks, according to an Earthwork Factsheet. The mine is also considered a source of major environmental contamination and the second most polluting mine in the US.

Native tribes as shareholders

However, the issue of tribal opposition and a mining project on an ecologically important river is not a simple one.

Donlin Gold operates under agreements with Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) landowners, Calista and The Kuskokwim Corporation (TKC). Calista is one of thirteen regional Corporations created to provide stewardship of ancestral lands and financial resources for Alaska’s native people.

The Yup’ik, Cup’ik, and Athabascan native groups are shareholders of the two regional bodies. Through the ANCSA, Calista owns 6.5 million acres of land in the YKD and Kuskokwim mountains. However, most of the land is split estate. While Calista owns a large portion of the sub-surface, the TKC is the corporation that owns majority of the surface rights.

In 1996, Calista and TKC issued a mining lease to mining company Placer Dome, which was later purchased by Barrick Gold and renamed Donlin Gold.

“Donlin Gold was conceived by Alaska Native land owners Calista Corporation and The Kuskokwim Corporation in order to improve lives throughout the region, including by providing the income needed for the equipment to support a subsistence way of life, such as clothing, gear, fuel, snow machines, boats, four-wheelers, and more,” Kristina Woolston, External Affairs Manager of Donlin Gold, said in an email.

However, tribal governments are saying that Calista and TKC entered into agreements without consulting shareholders.

“The decision to approve the development of Donlin was never put to the Calista shareholders, it was made by a Board of 11 directors swayed by misinformation [on the project’s potential environmental impact],” said Calista shareholder and citizen of Orutsararmiut Native Council Beverly Kikikaaq Hoffman.

“Many of us hoped that the Native Corporations created in 1971 would protect our land and our river and its tributaries from projects like Donlin. But sadly, they got caught up in the corporate mentality of making [money] almighty and, in my opinion, forgot the people they represent.”

Mongabay contacted Calista for a comment but received no response at the time of publication.

Donlin Gold has also been accused of not holding proper consultations regarding the project. However, the company denies this. According to Woolston, Donlin has held over 500 consultations with communities in the region since consultations began.

“We have long believed that a critical component to helping people understand the project is having open dialogue to address people’s questions and concerns,” said Woolston.

The mining company has adjusted its plans to address concerns regarding barge traffic along the Kuskokwim through the addition of the natural gas pipeline, and expanded its community relations team to regularly communicate with tribal entities, community leaders, and businessowners. The company promises to engage with tribes on environmental protection and provide jobs to locals.

“We want economic opportunities for all of our families, but not opportunities that will put fish, moose, caribou, seal, walrus, berries, plants and birds at risk; our food source,” a group of Indigenous women living in the region wrote in a letter to Calista.

Appeals to protect waters and lands

Unwilling to accept the mine without a legal battle, tribal leaders have challenged the issuance of the Federal Clean Water Act certification and the Pipeline Right-of-Way lease by Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources and Department of Environmental Conservation (ADEC), last year. The two appeals are currently in Alaska Superior court.

One of the tribal councils has appealed the Clean Water Act certification several times. This was given after the ADEC certified that there is reasonable assurance that the project to fill in wetlands, and any discharge which may result from it, will comply with the applicable provisions of the CWA and the Alaska Water Quality Standard.

However, an Administrative Law Judge found that the water quality standards for mercury will undeniably be exceeded by the project in numerous locations. Alaska’s superior court is currently allowing the ADEC time to review additional scientific information.

As for the appeal against the issued pipeline-Right-of Way lease permit, the case is currently ongoing with arguments that the state authorized the permit without a clear idea as to how many salmon streams could be impacted.

Donlin has already received key permits except for the Dam Safety certification needed to construct the tailings from federal and state agencies.

Should Donlin acquire the necessary permits and complete geological resource evaluation, the company will decide on an official date to begin its construction activities.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay