Written by: Simon Read

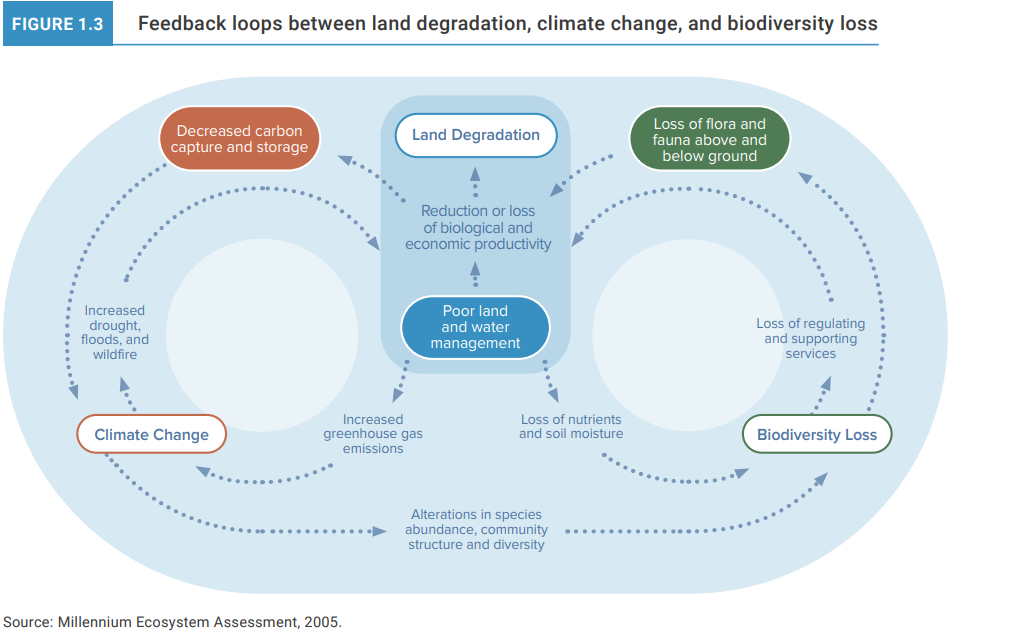

Scientists are becoming increasingly alarmed about humanity wrecking something very fundamental to all of us: the soil under our feet. Why? Because up to 40 percent of the land on Earth is now degraded, worsening climate change and causing hunger and poverty.

Land becomes degraded when poor farming practices lead to soil erosion, declining crop yields and a loss of biodiversity. This is contributing to global food insecurity, at a time when the United Nations (UN) is warning that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could leave some countries facing famine because of the loss of wheat exports from the region.

Chronic land degradation directly affects half the world’s population, according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). And the UNCCD predicts that if we carry on behaving as we are now, an additional area roughly the size of South America will become degraded by 2050.

Land crisis

“Conserving, restoring and using our land resources sustainably is a global imperative, one that requires action on a crisis footing,” the UNCCD’s Global Land Outlook 2 report warns. “Business as usual is not a viable pathway for our continued survival and prosperity.”

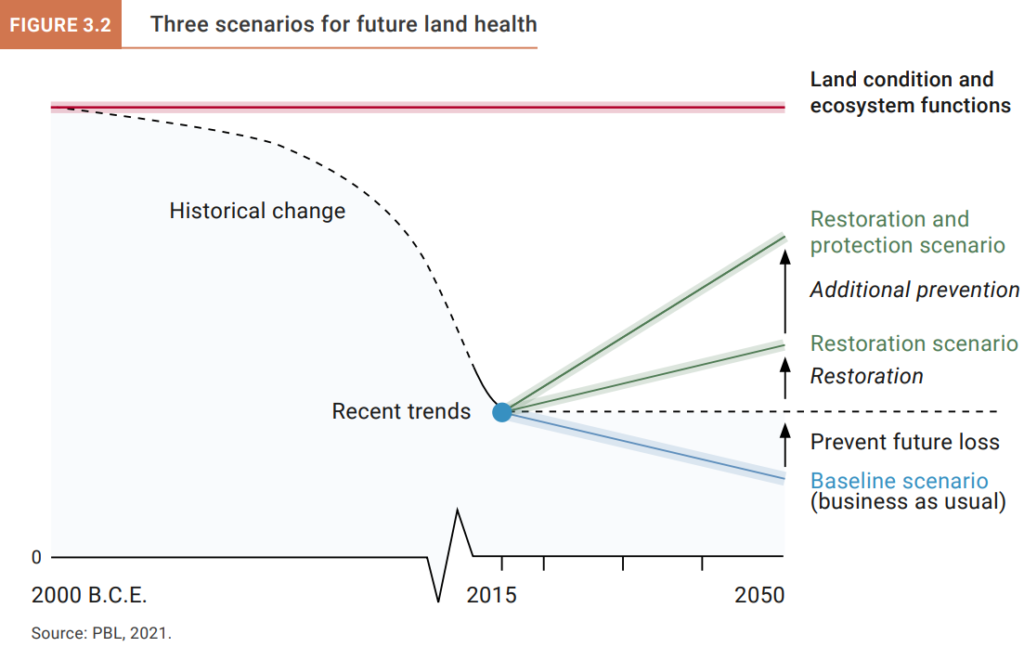

The report suggests hundreds of ways that governments can improve matters. It outlines three possible outcomes depending on whether we do nothing, embark on widespread soil restoration projects or go all out to protect and restore land across the planet.

“Modern agriculture has altered the face of the planet more than any other human activity,” UNCCD Executive Secretary Ibrahim Thiaw says. “We need to urgently rethink our global food systems, which are responsible for 80 percent of deforestation, 70 percent of freshwater use, and the single greatest cause of terrestrial biodiversity loss.”

In some cases, restoring soil will mean farmers can grow more food. But it can also help in the fight to control climate change by reducing deforestation. If more productive land is brought back to life, there should be less pressure on farmers to clear forests to make way for new croplands and pastures.

Better soils, better climate

Healthy soils and the plants that grow in them also store carbon, helping to counter global warming. When farmers abandon an area of degraded land, nature takes over, and as the land gradually recovers it removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

It’s a very slow process, but there are ways farmers might be able to speed it up, such as using soil for a more diverse range of plants, or spreading an additive called biochar. Biochar is a charcoal-like substance produced when organic matter is burnt at high temperatures in an oxygen-deprived environment. When it is added to soil, it has the potential to improve carbon storage and make the land more fertile.

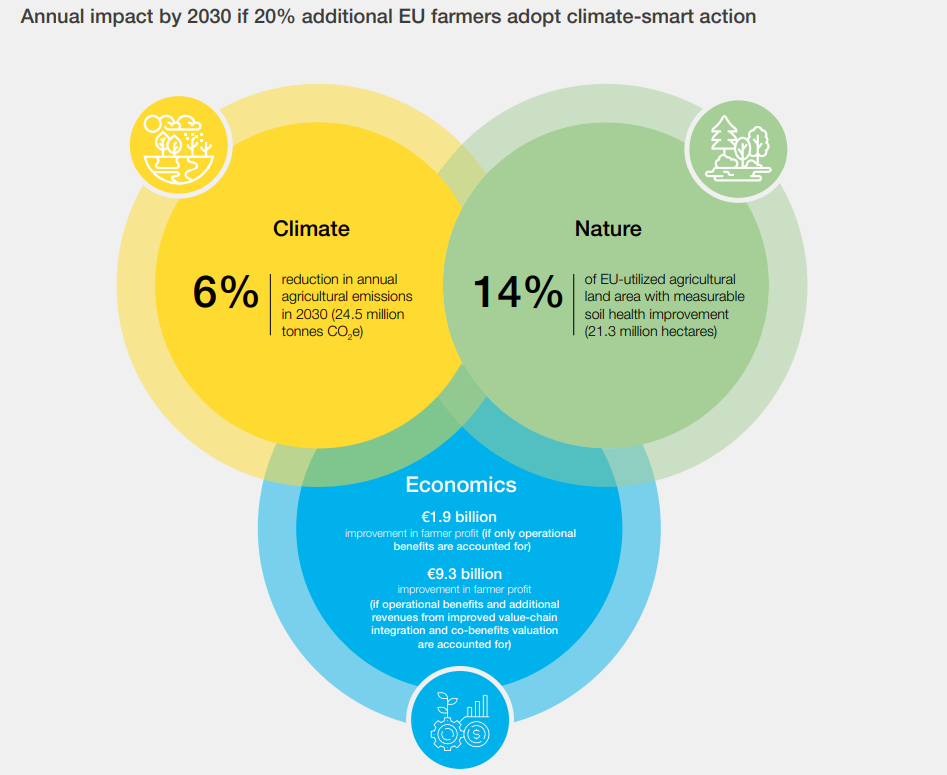

Getting farmers to switch to techniques that might restore soil is a huge challenge, but it could pay dividends. A World Economic Forum report shows that if the EU’s farmers receive support to take climate-smart actions, the bloc could cut its agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 6 percent, restore soil health to more than 14 percent of its farmland and boost farmers’ incomes.

Paying farmers to raise soil standards

The UK is encouraging farmers to improve soil quality as part of reforms to agricultural policy following Brexit. Much of the country’s soil has deteriorated as a result of intensive farming methods, including mechanization, ploughing up hedgerows and the increased use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

From 2024, the UK’s farmers will be paid if the soil on their land reaches higher standards. However, the complexity of measuring soil quality, and the length of time it takes to improve it, leads some to argue that it would be more effective to reward better farming practices, rather than pay for results.

Ways to solve the planet’s soil crisis are being developed, but getting the right incentives for farmers in place will be just the start of a long journey. Theresa Lieb, a Food Systems Analyst with GreenBiz Group, says she felt a “profound sadness” after visiting the US state of Minnesota to investigate the take-up of regenerative farming. Although Lieb met a handful of farmers working sustainably, conventional farming still has a strong hold in the area. “The overall landscape I observed during many hours behind the wheel is desolate. In an hour or more of driving I could count the number of fields using regenerative agriculture practices on one hand.”

Header Image Credit: Glen Carrie/Unsplash

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum