Written by: Erik Hoffner

January brought a pair of rough storms to the northeastern U.S. They hit when the tides were high and pushed higher than normal by rising sea levels, setting numerous high-water records and prompting Maine Governor Janet Mills to request a federal disaster declaration. These events, just three days apart, built on damage suffered during another storm during the December 2023 holidays and another during the previous December.

“Extensive” is the word that Peter Slovinsky, a marine geologist for the Maine Geological Survey, chose to describe the most recent damage during an interview with Mongabay. He pointed to an estimate that 60 percent of Maine’s working waterfronts were severely damaged. “We saw numerous seawall failures and erosion of anywhere between 15 to even up to 30 feet [4.5-9 meters] of coastal sand dunes, and massive bluff failures also,” Slovinsky said.

The common response to busted docks, condemned houses, shrinking shorelines, disappearing dunes and faltering bluffs has been to bolster the shore with ‘hard’ infrastructure like concrete jetties and breakwaters of imported boulders. But those interventions are expensive, carbon-intensive, and ultimately ineffective due to continual sea level rise.

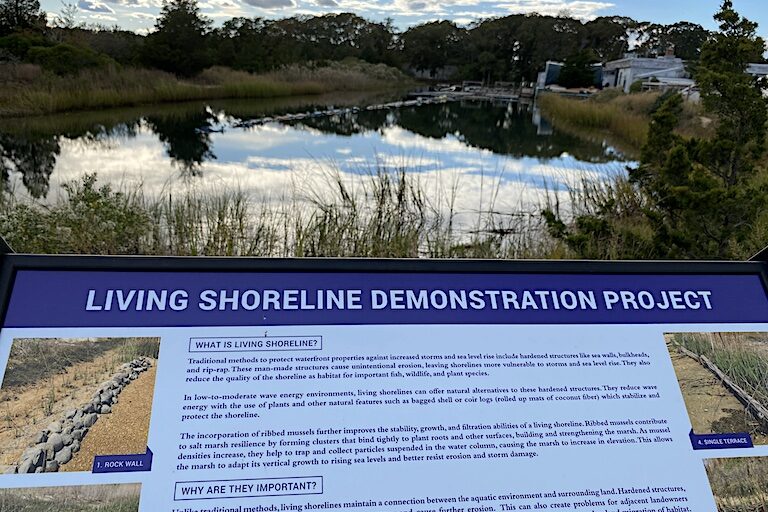

Increasingly, agencies like Slovinsky’s have been experimenting with a more natural and possibly more effective approach called living shorelines. The U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) defines these as “projects that connect the land and water to stabilize shorelines, reduce erosion, and provide valuable habitat that enhances coastal resilience.”

Such projects often take the shape of phalanxes of buried Christmas trees that shore up dunes, mesh bags of shells placed to protect mudflats from erosion, and salt-loving grasses and shrubs planted to stabilize nearshore areas.

Development of living shorelines is widely credited to the late Edgar William Garbisch Jr., a chemistry professor turned wetland restorationist who piloted the approach’s early methods and philosophy during the early 1970s in Chesapeake Bay. The aim is to protect coastal ecosystems like marshes and beaches with natural assets that create habitat while anchoring the shore. This method has gained increasing traction along much of the U.S. East Coast, from Georgia on north, as communities have begun to confront the impacts of human-caused climate change, including worsening storms and sea level rise, which is set to increase a further 0.6-1.2 m (2-4 feet) by 2100.

While Maine’s official experiments with such interventions at places like Popham and Pemaquid beaches have seen varying levels of success among their dunes and marshes, one Belfast area entrepreneur is innovating new ways of leveraging the living shorelines concept to protect another ubiquitous coastal feature: sandy bluffs.

On a cold November morning, contractor Paul Bernacki showed a Mongabay reporter around his latest project site on the Blue Hill Peninsula in Midcoast Maine, where a homeowner had hired him to preserve an eroding bluff along 2,000 ft (610 m) of shoreline. His vision for shoring it up differed greatly from others the property’s owner initially approached: “The engineers and their contractors wanted to kill all the trees on the shore, move the bank back 10 feet [3 m] at the top, and then pile 200 truckloads of rocks all the way around,” he said.

“Their solution to stabilization is to kill nature. Is that technically feasible for the whole coast of Maine?” Bernacki asked.

He said he doesn’t think so, and his team has been pairing a fresh take on the living shorelines best management practices with power tools to shore up this crumbling cliff and its line of oak trees and house in danger of tipping into the salt pond below.

The home is perched on one of Maine’s many so-called “erodible bluffs.” Despite the rocky shore postcard pictures, 40 percent of the state’s coast is classified as this mix of sand, rock and vegetation that’s vulnerable to wave action and scouring by wind-driven blocks of ice. Bernacki’s team shores up land like this not with imported rocks, but with natural and often local materials.

Among these are logs (sometimes including drift logs) and salt-tolerant plants often germinated from regionally wildcrafted seed stocks, plus imported materials like coconut fiber-based coir landscape fabric shaped into long tubes and filled with a matrix of soil and organics. These tubes, affectionately called “Tootsie Rolls,” are positioned behind rows of logs pinned down with rebar to form tiers and planted with salt-loving grasses like northern sea oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) or broomsedge (Andropogon virginicus).

Seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) and white yarrow (Achillea millefolium) are also planted, and on the bluff above these, perennial shrubs like winter berry (Ilex verticillata), Virginia rose (Rosa virginiana) and beach plum (Prunus maritima). Finally, rocks are placed among the logs to break up waves and scouring ice, until the plants’ roots get established.

This increasingly popular approach — which looks attractive while creating habitat for birds, bugs and nearshore creatures — often costs less than the imported rock or manufactured cement of seawalls and breakwaters, while being as effective or better. NOAA estimates that living shorelines can cost less than hard shorelines, both in terms of installation and maintenance, with costs ranging from less than $1,000 up to $5,000 per linear foot ($3,300-$16,400/m) of shoreline. Installing hard options, by contrast, typically ranges from $2,000 and up per linear foot ($6,600/m), according to The Maine Monitor. Maintenance of living shorelines costs about $100 per foot ($330/meter) annually, according to NOAA, while repairing hard shorelines costs from $100 to $250 per linear foot ($330-$820/m).

While some say it’s a winner on cost, that’s also likely in terms of carbon if one considers a life-cycle analysis of living shorelines, which is where Bernacki stresses the big difference lies. “The carbon footprint of our work is minimal for the dollar,” he says.

Following the recent storm trio, he reported that his team’s current project withstood the elements well, with no damage to the newly established structures or the bluff, which was also helped by the site being more protected than if it were right on the bay. Still, some of the less salt-tolerant plants higher up on the bluff were inundated by the tide, and may need replacing if they don’t green up in the spring.

Perhaps because Maine has been slower than other states to enact broad regulations for the various situations that living shorelines could apply to, like erodible bluffs, such private- and contractor-led efforts are getting greater attention from landowners, said coastal geologist Slovinsky. “I’ve had more people than ever in the last couple of years call and say, ‘Hey, my bluff is eroding, but I don’t want to build a seawall, what do I do?’ So, I point them to our coastal property owner guide that I wrote a couple years ago,” he said.

In nearby New Hampshire, which has worked living shorelines into state regulations already, there’s a similar level of interest and several projects underway at sites like Cutts Cove in Portsmouth, which also weathered the recent storms well. And, like Bernacki’s team, they’ve made an effort to incorporate naturally available and sometimes free resources found onsite in their construction, like local plants, tree stumps and drift logs.

“The thinking is that over time, as the tree stumps and drift logs decompose, the near vertical riprap sill will slowly shift into a more gradual and natural slope,” said Grant McKown, a coastal habitat research associate for the Jackson Estuarine Laboratory at the University of New Hampshire, via email. “Additionally, the use of drift logs and trees in the sill construction enhances the physical heterogeneity of the sill, providing additional refuge for nekton (mobile aquatic animals) during high tide and additional surface area for macroalgae (like Fucus and Ascophyllum) to colonize,” he wrote.

Is it enough to successfully hold back the rising tides, though?

Back in Maine, results vary. One Freeport-area homeowner reported in January that their $40,000 living shoreline had been washed away. But while Bernacki’s current project fared fine, he was philosophical on the question: “Success to me is restoring this habitat — instead of destroying more habitat to protect property,” he said. “That, you really can’t justify.”

So, everything is on the table after the recent spate of storms, including the old standby, Slovinsky said: “One of the things I’m pessimistic about is the response that we’re seeing thus far from these storms: more rock,” in the form of rapidly rebuilt seawalls and breakwaters.

It’s probably going to take advocacy and many more contractors to push his state to roll out a regulatory regime for naturally protecting its iconic shore, both for official and private projects. But momentum is building among Maine’s landowners, at least, who are increasingly willing to spend more for waterfront property despite sea level rise: “I’m getting a new call once a week,” Bernacki said.

So, like the wetland plants sown by his crew, the number of landowners interested to employ natural solutions, rather than piling up yet more rocks against an ever-rising tide, is also growing.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay