Courtesy of Landscape News

Written by: Monica Evans

To manage its oceans better, the Seychelles uses an unlikely resource to come up with the cash to do so: its national debt. As of 26 March 2020, the island nation has used an innovative financial model to turn 30 percent of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) into marine protected areas.

It’s not a new idea, says Angelique Pouponneau, the CEO of the Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT), which worked with international environmental NGO The Nature Conservancy (TNC) to develop the financial mechanism, known as blue bond. “Debt for nature swaps have been around for a very long time, but it’s been predominantly terrestrial based [known as a green bond]. This one was different because for the first time it was ocean space–related.”

Ocean protection can be a complex and expensive business. Costly research and consultation is required for marine spatial planning and mapping out an exclusive economic zone. Designating areas and resources for protection has major implications for the people whose livelihoods depend on them. For many countries, the upfront costs are simply unaffordable.

How do the swaps work? Countries like the Seychelles with traditionally poor credit ratings with banks pose a considerable risk to lenders that the debt will never be paid back. When the countries go to borrow money, they’re charged very high interest rates.

Lenders might also be willing to sell the debt on for less than what it’s worth, in order to recoup at least some of their outlay – and therein lies the solution.

“Being able to buy back debt at a discount is the secret sauce,” says Rob Weary, deputy managing director of TNC’s Blue Bonds for Conservation program.

In 2016, TNC bought a portion of the Seychelles’ debt off its lenders at reduced cost. The Seychelles government agreed to pay the debt back to TNC over a defined period of time, and to funnel the savings from its lower interest rates into ocean protection, including making 30 percent of its exclusive economic zone marine protected areas, as it has now achieved.

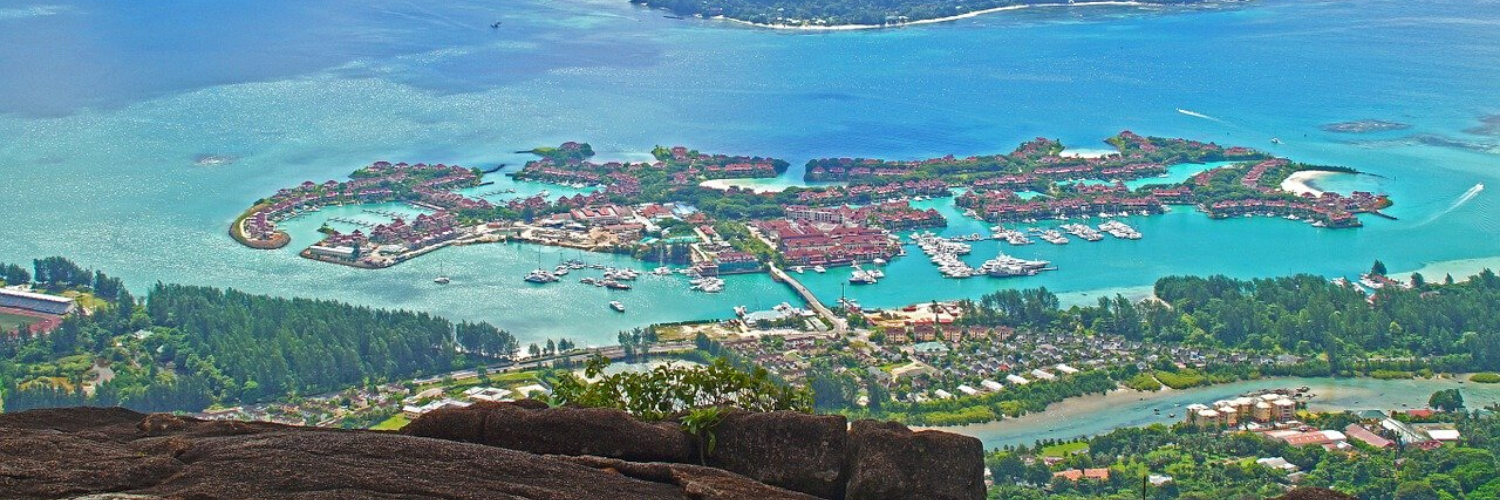

The Seychelles consists of 115 small islands in a 1.3 million-square-kilometer stretch of the equatorial Indian Ocean. Fishing brings in 97 percent of its annual export earnings, and its residents consume 53 kilograms of fish per capita per year.

In October 2018, the Seychelles government issued the world’s first “sovereign blue bond,” a more direct arrangement where investors purchase bonds in the knowledge that the money will be used specifically for projects that increase sustainable fisheries in the country. To lower the interest rates, the bond is partially guaranteed from the World Bank and a concessionary loan from the Global Environmental Facility.

SeyCCAT is responsible for administering both of these funds.

So far, a key focus for the bonds’ use has been the development of a marine spatial plan, which among other things determines the areas to be set aside for marine protection. That was challenging, says Weary, because of the politics of the process. “You’re getting all the users of that space around the table, and they don’t necessarily trust each other,” he says. “And you have to develop those relationships. So it takes a long time.”

The trust has also funded a wide range of projects on marine protection topics, from fisher-led seasonal fishery closures to boost species’ stocks, to a blue economy entrepreneurship assessment, to tracking the migration patterns of the native sooty tern (Sterna fuscata).

In one of the funded activities, which demonstrates the scale and transboundary nature of ocean pollution, a crew of volunteers traveled to the remote island of Aldabra to clean up plastic waste. “Over a five-week period, they removed 25 tons of waste from this island,” says Pouponneau. “There were 55,000 flip-flops. And by the way, there are only six people living on this island, and they’re all researchers – so it’s definitely not their flip-flops.”

In the past year, the concept has seen some traction worldwide, with both the Nordic Investment Bank and the World Bank launching their own blue bonds to address specific marine protection issues, such as wastewater treatment, water-related climate change adaptation and plastic waste pollution in oceans.

TNC, for its part, aims to do debt-restructuring deals with 20 countries in the next five years, and Weary hopes to see the development of an international blue bond market, similar to the existing one for green bonds. “I think we can really scale this up,” he says.

Pouponneau says it’s increasingly crucial that blue bond schemes invest in projects that are climate-smart. She describes a site visit to a sooty tern nesting site, in which she and her colleagues noticed an unusual number of dead chicks. They returned to ascertain what was going on and realized that ocean temperature rise was affecting the terns’ food supply, “because they’re dependent on small pelagic fish to eat,” she says, “and pelagics are very temperature-oriented in terms of where they go.”

“It really showed how if you’re devising solutions to these ocean management and conservation, you really need to think about doing it in a changing climate,” says Pouponneau.