Written by: Jörg Wiedenmann and Cecilia D’Angelo

Ocean heatwaves cause vast coral bleaching events almost every year due to climate change, threatening reefs around the world. The high water temperatures stress reef building corals, causing them to eject the photosynthetic algae that reside in their tissue. Losing these brownish-coloured plant cells lets the coral’s white limestone skeleton shine through, turning reefs ghostly white.

But when some corals bleach, they undergo a mysterious transformation that has confounded scientists. Rather than turning white, these corals emit a range of different neon colours. Colorful bleaching, as it’s known, was covered in the documentary Chasing Coral, which showed a whole reef turning fluorescent. The underwater photographer who documented the event said:

“It was as if the corals were screaming for attention in vivid colour, trying to protect themselves from ocean heatwaves. We’d witnessed the ultimate warning that the ocean is in trouble.”

In new research, we’ve finally uncovered why corals do this.

Solving a coral conundrum

We knew that the appearance of unusually fluorescent corals was linked to bleaching. But why didn’t all corals suddenly become more colourful? And why did they only seem to appear during certain bleaching events? Things got even stranger when we tried to expose corals in the laboratory to experimental heat stress.

In our first trials, instead of becoming more colourful, they just bleached white. But after conducting more lab experiments with the help of our students Elena Bollati and Rachel Alderdice, we found an answer.

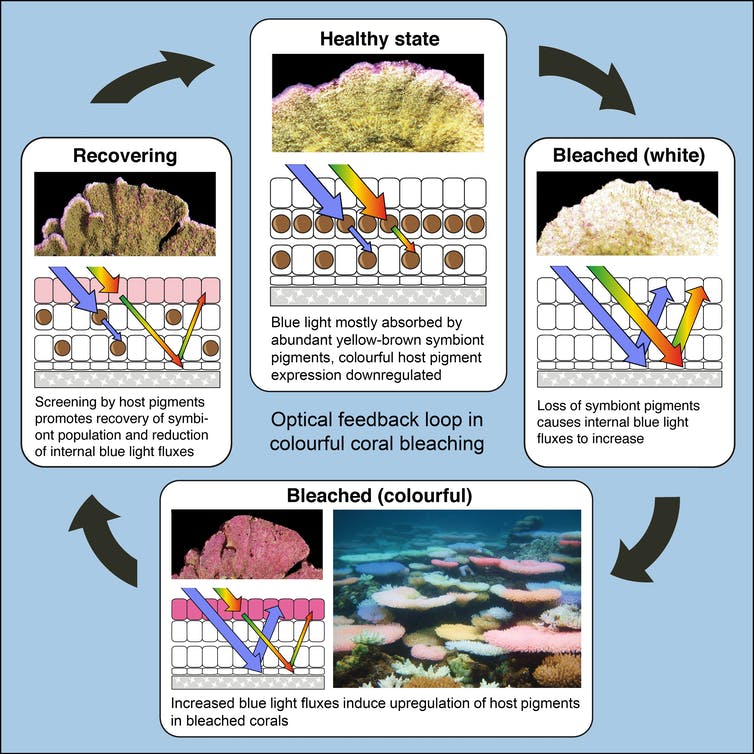

In healthy corals, much of the sunlight is absorbed by the photosynthetic pigments of the algae. When corals lose their algae due to stress, the excess light travels back and forth inside the coral tissue, reflected by the white skeleton. The algae inside coral can recover after bleaching, once conditions return to normal. But when the coral interior is lit up brightly like this, it can be very stressful for the algae, potentially delaying or even preventing their return.

If the coral cells can still carry out at least some of their normal functions during bleaching, the increased internal light levels boost the production of colourful pigments which protect the coral from light damage, forming a kind of sunscreen layer that allows algae to return. As the recovering algae start absorbing light for photosynthesis again, light levels inside the coral drop, and so the coral stops producing as much of these colourful pigments.

But it’s not just heat stress that can cause colourful bleaching. Corals and their algae are very sensitive to changes in nutrient levels in their environment. When there’s too little phosphorous or too much nitrogen in the water – something that can happen when fertiliser runs off from farmland into the ocean – strong colourful bleaching can occur.

A brighter future for reefs

Using satellite data, we reconstructed the temperature profiles for known colourful bleaching events. We saw that they tend to occur after brief or mild episodes of heat stress. When corals are exposed to severe or prolonged temperature extremes, they tend to bleach white. That’s why we only see bright neon colours in particular bleaching episodes, when conditions are just right.

Different members of the coral community can display different colours during these events, while some species don’t produce these colourful protective pigments at all. But even within coral species, there can be different colour variants that result from differences in their genetic makeup.

These variants have evolved to give species different strategies to deal with light, depending on where they grow on the reef. For corals in shallower water it’s beneficial to invest a lot of energy in producing the colourful sunscreen. At greater depths or in shaded areas where light stress is lower, corals that produce less of the protective pigment are better off as they can save their energy for other useful purposes. Even so, these different variants often occur side-by-side, which is why some corals bleach colourful while their neighbours turn white.

The good news is that colourful bleached reefs seem more likely to recover than corals that bleach white, since they tend to appear when heat stress isn’t so severe and the colourful pigments themselves offer protection. Reports suggest that colourful bleaching occurred on some parts of the Great Barrier Reef in March and April 2020, so some patches of the world’s largest reef system may have better prospects for recovery after the recent bleaching.

Now that we know that nutrient levels can affect colourful bleaching too, we can more easily pinpoint cases where heat stress might have been aggravated by poor water quality. This can be managed locally, whereas the ocean heat waves caused by climate change will need global leadership. Together, these actions can secure a future for coral reefs.