Written by: Colin Sytsma

The global spread of social media has created unparalleled opportunities for wildlife traffickers to advertise their illicit wares to potential buyers around the world. Traffickers can use platforms like Facebook or Instagram not only to post pictures of animals for sale, but also to expand their networks thanks to Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven algorithms that suggest friends and groups.

Social media, and AI, can also be valuable tools for conservationists and law enforcement.

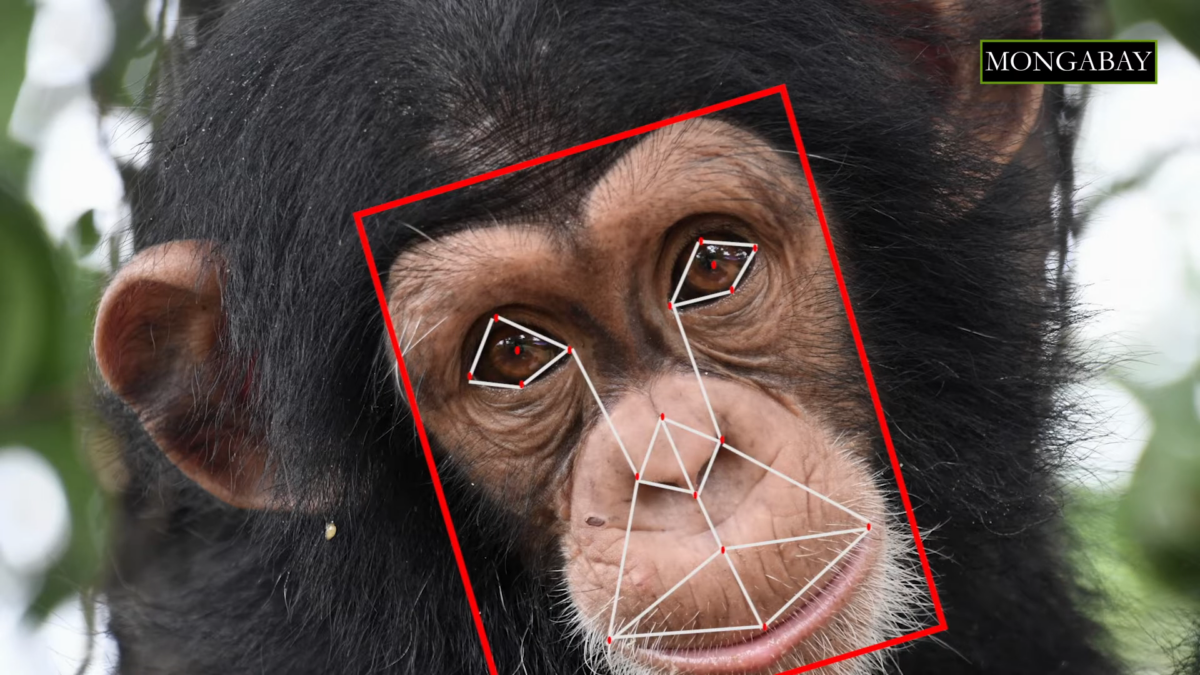

Networks of algorithms trained to spot patterns can mine data, identify objects, or even spot signs of sex trafficking and other crimes in images. One of the best-known, and most controversial uses of the technology is facial recognition, in which programs use biometric markers to identify people in digital images.

In conservation, AI can be used to identify land-use change, or even individual animals based on unique markings on their bodies. In animals like chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, AI is proving effective in identifying and tracking individuals’ faces.

Via her project ChimpFace, Allie Russo, a conservationist with a background in data analysis, is striving to harness the power of AI in the fight against ape trafficking.

Image by Tambako The Jaguar via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0).

According to the United Nations’ Great Apes Survival Partnership (GRASP), roughly 3,000 great apes are trafficked live from Africa or Southeast Asia every year.

Much of the illegal trade in wildlife now takes place online. A trafficker or great ape distributor will post an image of a baby chimpanzee for sale. Often, the same chimpanzee will later appear on someone’s social media account. But manually searching and comparing images is a laborious process. And alternative forms of evidence, such as DNA, are costly and difficult to obtain.

ChimpFace uses an algorithm to determine if chimpanzee faces in images posted by traffickers match up with images later posted to social media accounts. If the software finds a match, it serves as evidence that can help corroborate who sold a chimpanzee and where it ended up.

After participating in a competition organized by Conservation X Labs, a company that looks for high-tech solutions to conservation problems, Russo was connected with Colin McCormick. McCormick, one of Conservation X Labs’ technical advisers, made the programming part of ChimpFace a reality.

Using thousands of images of baby chimpanzees collected by conservationists, McCormick manually annotated where the face shows up within the image. He uses these images to train a computer program to identify faces, similar to how facial recognition programs for humans work. With repetition, he can fine-tune the algorithm to accurately detect the presence of a baby chimpanzee face in an image.

The software is just beginning to be tested, but ultimately its developers aim to provide information that Interpol or local law enforcement can act upon.

ChimpFace is only able to search publicly available images, meaning that if a trafficker has a private Facebook or Instagram profile, the images remain hidden. But with many traffickers advertising publicly, the hope is that the program will provide law enforcement with a new type of evidence that can help confirm that an individual ape was illegally captured from the wild and sold.

ChimpFace has recently partnered with Liberia Chimpanzee Rescue and Protection (LCRP) to further strengthen the use of the software. Support from sanctuaries like LCRP, which sees an average of one new chimpanzee a month, is important because if the software does help secure prosecutions for traffickers, rescued animals will need a place to go.

Russo says she hopes that one day ChimpFace can be scaled up to add additional target species such as tigers, lions, gibbons, or any species that is in danger of being illegally trafficked online.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay