Written by: Johnny Wood

The natural beauty of undersea corals seems far removed from the factory-like world of automated mass production. But an enterprising reef scientist is combining the two in an effort to regenerate the world’s reefs.

Although seemingly disparate, both of these worlds are familiar to coral biologist Taryn Foster, as she is a research associate at the California Academy of Sciences and before that worked in her family’s masonry manufacturing business.

Concerned about the damaging impact of climate change on reef ecosystems, she founded Coral Maker, which says it could manufacture 1 million coral skeletons each year to restore destroyed or declining reefs. Current annual production rates are about 25,000, according to the organisation.

The coral production line

To date, reef restorations tend to be localised projects, using techniques like coral gardening – growing corals in nurseries to repopulate reefs – which need lots of manpower and take time.

Adopting a unique assembly-line approach, Foster and her team have drawn on the help of robots to mass produce corals ready to repopulate reefs on a vast scale.

Although still in its infancy, the new process starts with a specially designed dome-shaped “coral” skeleton, produced using dry-casting – a traditional masonry manufacturing technique that could potentially produce around 4,000 stone coral skeletons daily. The next step on the production line involves a robotic arm inserting seed plugs with live coral fragments into the skeleton, which can then be situated on a reef system to mature.

Automating the process eliminates manual tasks, speeds up the seeding process and removes many of the bottlenecks in achieving reef-scale restoration.

What’s the problem?

Although brightly coloured corals look like plants, they are actually animals that feed off algae living in their tissue. Coral reefs are among the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, and support about a quarter of all marine life.

Numerous marine species depend on healthy reefs, which also provide a rich food source for fishermen and form the basis of a thriving diving and tourism industry. Reefs also form natural barriers to protect coastal regions from heavy seas.

Credit: NOAA

But coral reefs are under threat from the worsening climate crisis, which is disrupting the synergy between coral and algae. Warming ocean waters stress the corals, leading them to expel the algae – an event known as coral bleaching. Without this nutrition, the coral weakens and can eventually die.

Add to this pollution, trawling damage and other threats, and reefs appear to face a bleak future if action is not taken.

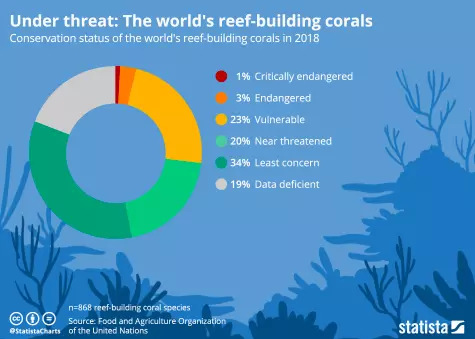

Credit: Statista

Almost half of the world’s reef-building coral species are under threat, according to the UNFAO. This includes 1 percent on the critically endangered list, and more than a quarter of global reefs either endangered or vulnerable.

New research presented at the Ocean Sciences Meeting 2020 predicts that warming ocean temperatures and acidification could cause nearly all existing reef ecosystems to disappear by the end of the century.

“By 2100, it’s looking quite grim,” Renee Setter, a University of Hawaii Manoa biogeographer who presented the findings, explains in an ACU statement.

“Trying to clean up the beaches is great and trying to combat pollution is fantastic. We need to continue those efforts,” he says. “But at the end of the day, fighting climate change is really what we need to be advocating for in order to protect corals and avoid compounded stressors.”

With the help of automation, seeding new coral reefs could take months instead of years. But while innovation offers a way to preserve reefs for coming generations, ultimately the solution lies in reducing our carbon emissions so that nature can be left to take care of producing new corals.

Header Image Credit: Matt Curnock/Coral Reef Image Bank

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum