Written by: Enric Sala

2021 ought to be the “super year” for nature, where we collectively agree on how to deal with the greatest risk to humanity: we have become totally out of balance with nature. But there is a solution that is scientifically proven and cost-effective, and new research has found a way forward.

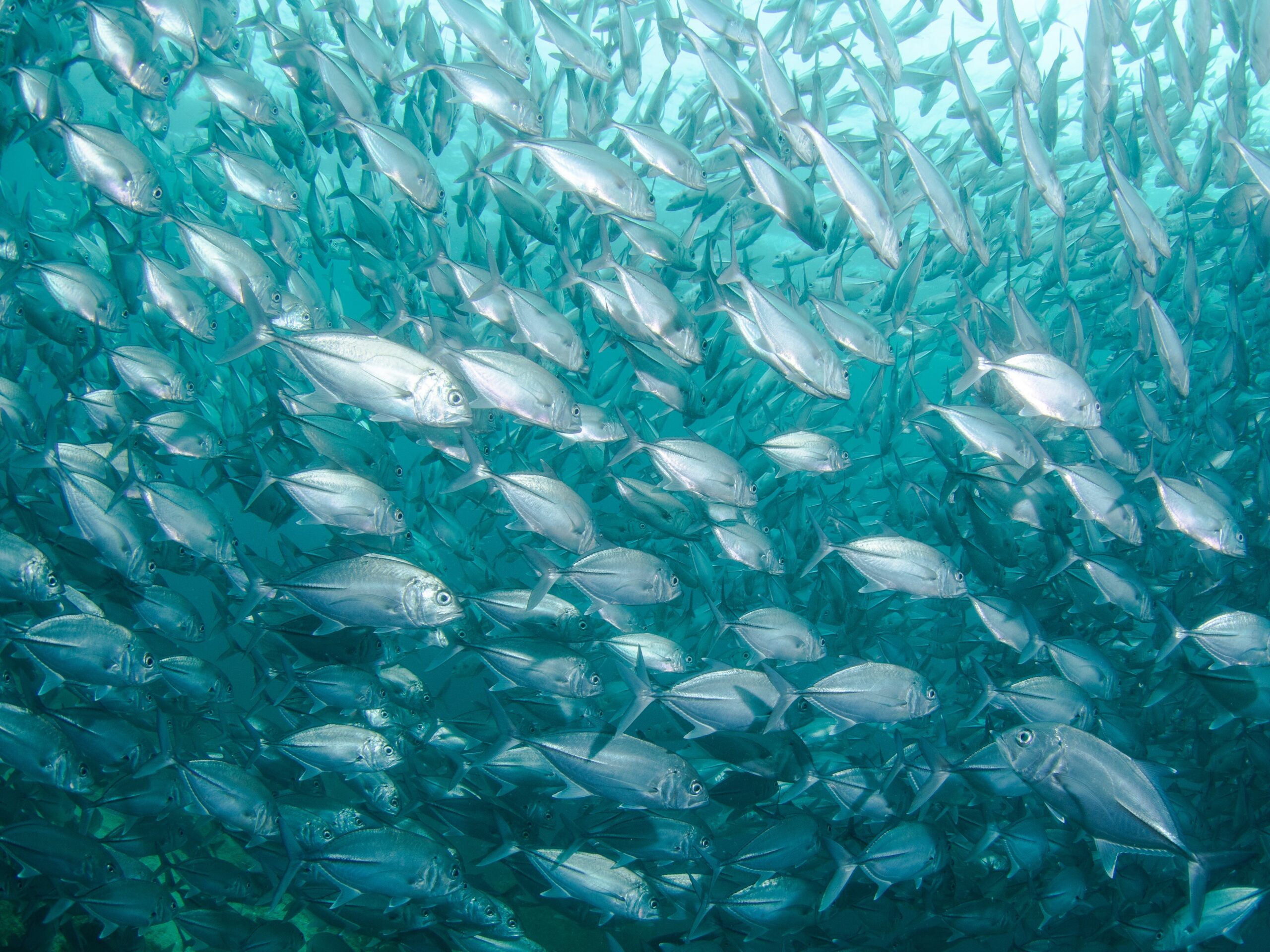

We’ve already lost 60 percent of terrestrial wildlife and 90 percent of the big ocean fish. Approximately 96 percent of all mammals on earth are humans and our domesticated livestock. Only 4 percent is everything else, from bears to elephants to tigers. We now risk the extinction of 1 million species during this century. Losing these species and all the goods and services they give us would mean the collapse of our life support system and everything we care about and need to survive: our food, our health, our economy, our security – everything.

The good news is that we can still avert this catastrophe. In October this year, the world’s countries will meet at the UN Biodiversity Conference in Kunming, China, to agree on how much space we humans are willing to give up to all the rest of the species with whom we share this planet. The ocean must become a more central character in this change. It is a victim of climate change – due to ocean warming and acidification – but it can also be a big part of the solution. However, despite the serious threats to our ocean life support system, presently only 7 percent of the global ocean is under some kind of protection. How much more do we need to protect?

Some argue that we cannot protect more ocean because soon we will need to feed 10 billion people – they recommend we need to develop a new “blue economy”. But this is a myth. We cannot take more fish out of the ocean by fishing more. And we cannot have a blue economy from a dead ocean. Already over three-quarters of fish stocks are fished beyond sustainable limits, and The World Bank suggests that we can only catch more fish if we cut almost in half the effort the world spends fishing.

This perceived trade-off between extraction and protection is what prompted me to assemble a team of colleagues a couple years ago, to calculate how much of the ocean we need to protect, and which areas should be protected to maximize benefits for people and planet. The science is clear: the more biodiversity there is, the more benefits the natural world gives us. So, we need to protect whatever wild is left, and restore what we have degraded.

On land, restoration can be accelerated by replanting native vegetation or reintroducing large animals, but in the ocean, the fastest way to restore balance is to let the ocean do it itself. When we close areas to fishing and other damaging activities, the biomass of fish increases on average six-fold within a decade. Thus, our team developed a new mapping tool to identify the areas that, if fully protected from damaging activities, would give us the greatest gains. Our main findings are the following:

1) More protection = more food

If we protect the right areas in the ocean, they would help replenish the surrounding areas so that the global fishing catch would increase globally up to over 8 million metric tonnes (or 10 percent of the global catch in 2018). So there goes the myth that we cannot protect more because we need to catch more fish. It is, in fact, conservation that will result in more fish.

2) More protection = less ocean carbon emissions

Our research found that the seafloor, which we thought was the largest carbon store on our planet, has been turned into a source of carbon emissions. Bottom trawlers plow around 5 million km2 of the seafloor (an area over twice the size of Greenland) every year with huge and heavy nets, disturbing the sediment and the carbon in it. Some of that carbon, when disturbed and resuspended in the water, turns into carbon dioxide – a greenhouse house that can stay in the air for 1,000 years.

The most shocking finding was that CO2 emissions from bottom trawling are similar to those of global aviation. There is a huge opportunity here, to protect the seafloor and precious ecosystems from bottom trawling, and at the same time reduce massive carbon emissions. The carbon that would not be emitted year after year could be sold by countries as carbon credits, and that capital could then be used to finance ocean protection.

3) We must protect at least 30 percent of the ocean

Our research found that, no matter how we value marine life vs food vs climate, we must protect at least 30 percent of the global ocean. We would protect less than that only if humanity decided that marine biodiversity was something we did not want – which we know is suicidal. Identifying which areas to protect depends on how countries value each of biodiversity, fisheries and climate change mitigation. Our new mapping tool allows stakeholders to give different values to the different objectives and calculate multiple benefits. Every option yields a different map. But no matter how one values these three areas, the vast majority of the priorities for ocean conservation are located within countries’ 200 mile exclusive economic zones.

4) Global collaboration is more efficient

Importantly, our new research shows that if countries protect areas based on global priorities, it would take less than half of ocean area to achieve the desired benefits than if every country only cares about their national priorities. Going alone would take more effort and be costlier.

Our results support the global target of at least 30 percent of the ocean to be protected by 2030 that is being proposed by over 50 nations and the European Commission as one of the main targets for the Kunming nature agreement later this year. If we give the ocean the space it needs, it will feed us, boost food security and help us avert climate catastrophe. That is the blue economy we need, the economy of a living ocean.

Republished with permission from World Economic Forum